Boston Corbett

Boston Corbett | |

|---|---|

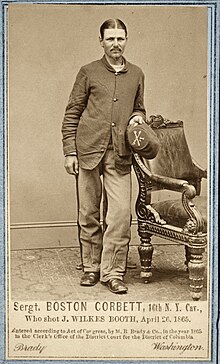

Corbett c. 1864–1865 | |

| Birth name | Thomas H. Corbett |

| Nickname(s) | The Glory to God Man Lincoln's Avenger |

| Born | January 29, 1832 London, England |

| Disappeared | c. May 26, 1888 (aged 56) Neodesha, Kansas |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank | Sergeant |

| Unit | 12th New York State Militia 16th New York Cavalry Regiment |

| Battles / wars | American Civil War |

| Signature | |

Sergeant Thomas H. "Boston" Corbett (January 29, 1832 – disappeared c. May 26, 1888) was an English-born American soldier and milliner who killed John Wilkes Booth, the assassin of President Abraham Lincoln on April 26, 1865. Known for his devout religious beliefs and eccentric behavior, Corbett was reportedly a good soldier and had been a prisoner of war at Andersonville Prison. Corbett shot and mortally wounded Booth when his regiment surrounded the barn Booth was hiding in. For his actions, the American media and public largely considered Corbett a hero.

Corbett drifted around the United States before he was committed to Topeka Asylum for the Insane after being declared insane in 1887. Corbett escaped and disappeared in 1888.

Early life and education

[edit]Corbett was born in London, England, on January 29, 1832, and immigrated with his family to the US in 1840. The Corbetts moved frequently before settling in Troy, New York. As a teenager, Corbett began apprenticing as a milliner, a profession that he would hold intermittently throughout his life. As a milliner, Corbett was regularly exposed to the fumes of mercury(II) nitrate, then used in the treatment of fur to produce felt used on hats. Excessive exposure to the compound can lead to hallucinations, psychosis and erethism.[1] Historians have theorized that the mental issues Corbett exhibited before and after the Civil War were caused by this exposure.[2]

Family and religion

[edit]After working as a milliner in Troy, Corbett returned to New York City.[3] In the early 1850s, Corbett met Susan Rebecca, who was thirteen years his senior, and they married. The couple migrated, and on June 9, 1855, Corbett became an American citizen, taking the oath in a Troy courthouse. Corbett had a hard time finding and keeping work in Richmond, Virginia, in large part because of his vociferous opposition to slavery. His wife became ill, and, as they were returning to New York City by ship, she died at sea on August 18, 1856. The body continued to New York, where her death was recorded and she was buried. Following her death, he moved to Boston. Corbett became despondent over the loss of his wife and, according to friends, began drinking heavily.[4] He could not hold a job and eventually became homeless.[1][5] After a night of heavy drinking, he was confronted by a street preacher whose message persuaded him to join the Methodist Episcopal Church. Corbett reportedly encountered some evangelical temperance Christians and was detained by them until he sobered up, undergoing a religious epiphany in the process.[6]

In 1857, Corbett began working at a hat manufacturer's shop on Washington Street in downtown Boston. He was reported to be a proficient milliner but was known to proselytize frequently and stop work to pray and sing for co-workers who used profanity in his presence. He also began working as a street preacher and would sermonize and distribute religious literature in North Square.[7] Corbett soon earned a reputation around Boston for being a "local eccentric" and religious fanatic.[1][2] by the summer of 1858, Corbett fell in with members of the Methodist Episcopal Church, becoming a proselytizer and street preacher. On July 16, 1858, Corbett, while trying to remain chaste, struggled against sexual urges and began reading chapters 18 and 19 in the Gospel of Matthew ("And if thy right eye offend thee, pluck it out and cast it from thee....and there be eunuchs, which have made themselves eunuchs for the kingdom of heaven's sake"). Years later, a friend recounted Corbett saying "that the Lord directed him, in a vision or in some way, to castrate himself." Corbett castrated himself with a pair of scissors.[2] He ate a meal and attended a prayer meeting before someone was sent for medical treatment.[8] Corbett was released on August 15, and a friend recorded that "he was very much gratified with the result as his passion was not trouble any more...his object was that he might preach the gospel without being tormented by his passions."[9] After being baptized on August 29, he subsequently changed his name to Boston, the name of the city where he was converted.[10] He regularly attended meetings at the Fulton and Bromfield Street churches where his enthusiastic behavior earned him the nickname "The Glory to God man".[3] In an attempt to imitate Jesus, Corbett began to wear his hair very long (he was forced to cut it upon enlisting in the Union Army).[11][12] Corbett was described as friendly and open, helpful to those he saw in need but also quick to condemn those he thought were out of step with God.[13] Corbett routinely gathered up drunken sinners from the New York streets and took them to his room, where he would sober them up and feed them, restoring their health and also trying to help them find work. He continually expended all his own money and frequently borrowed from friends. When his hat-making boss asked Corbett about his lack of decent clothes for himself, Corbett always said he was "doing the Lord's work." His boss later described him as "a good man, for all of his faults were of the head, and not of the heart."[14]

Military career

[edit]Enlistment in the Union Army

[edit]

On April 19, 1861, early in the American Civil War, Corbett, who was anti-slavery,[15] enlisted as a private in Company I of the Union Army's 12th New York State Militia. Corbett's eccentric behavior quickly got him into trouble. He always carried a Bible with him and read passages aloud from it regularly, held unauthorized prayer meetings, and argued with his superior officers.[16] Corbett also condemned officers and superiors for what he perceived as violations of God's word. In one instance, he verbally reprimanded Colonel Daniel Butterfield for using profanity and taking the Lord's name in vain. He was sent to the guardhouse for several days but refused to apologize for his insubordination.[17] Due to his continued disruptive behavior and refusal to take orders, Corbett was court-martialed and sentenced to be shot. His sentence was eventually reduced, and he was discharged in August 1863.[18] Corbett re-enlisted later that month in Company L, 16th New York Cavalry Regiment. On February 26, 1864, he was demoted to private as punishment for an unknown incident.[19]

Andersonville

[edit]Despite his religious-oriented eccentricities, Corbett reportedly was a good soldier. On June 24, 1864, after Confederate States Army troops led by John S. Mosby in Culpeper, Virginia had captured a good number of Corbett's comrades, Corbett continued to fire at the enemy from behind a persimmon tree and in a ditch with a seven-shooter repeating rifle. Three attempts were made to capture him before success was finally had when he ran out of ammo. Once Corbett was overtaken, one of the junior officers leaped from his saddle, enraged at Corbett's persistence, knocked the Spencer rifle from Corbett, and aimed a pistol at his head. Captain Chapman objected, "Don’t shoot that man! He has a right to defend himself to the last!" Corbett later related to friends that the man who saved his life was Mosby, though this is dubious.[20]

Corbett was to be a prisoner of war at Andersonville Prison. While on the way to Andersonville, the following incident happened, told by a fellow prisoner of Corbett's named William Collins:

At Macon there were about a thousand prisoners who had arrived ahead of us. The train we were on unloaded our thousand making 2000 in all. We were taken to an old pasture or common near the railroad tracks where a furrow was ploughed around it for a deadline. There was a small stream of water close to the guard line and the prisoners made a rush for it, most of them had no water for many hours, but the guards kept them back. One of the more venturesome than the rest got through the line and attempted to fill his canteen. He was immediately shot in the arm with buckshot by one of the guards. He was pushed back among our men and laid under a tree. The wounded man was suffering greatly and called for water to ease his pain, but none had any in his canteen. Boston Corbett stepped out of the ranks, having been unable to stand silent any longer. He crossed the deadline, filled his canteen in the stream and gave the wounded man a drink. The guards continually threatened him with death, but Corbett ignored them and went about his business. Despite their threats he returned unharmed and rejoined the ranks of prisoners. The cheers of the soldiers at this brave deed could have been heard one mile away, but Corbett seemed to think it was not out of the ordinary. It was the bravest deed that I had seen during the war. We arrived at Andersonville prison the next day.[citation needed]

Corbett met Richard Thatcher, a fellow POW who described Corbett as having "qualities that challenged my admiration, even more than the heroism he was capable of displaying in the battlefield. He read passages from the Scriptures to me, and spoke words of sound and wholesome advice, from which I began to learn that he was one who had the courage of his convictions."[21] Corbett, among others, led prayer meetings and patriotic rallies to boost morale, according to John McElroy's eyewitness account in his 1879 memoir Andersonville.[22]

After five months, Corbett was released in a prisoner exchange in November 1864 and was admitted to a military hospital in Annapolis, Maryland where he was treated for scurvy, malnutrition and exposure.[17] Upon Corbett's return to his company, he was promoted to the rank of sergeant. Corbett later testified for the prosecution in the trial of the commandant of Andersonville Prison, Captain Henry Wirz.[23][24]

Pursuit and death of John Wilkes Booth

[edit]

John Wilkes Booth shot President Abraham Lincoln, on April 14, 1865; Lincoln died the next day. On the night Lincoln was shot, Corbett's regiment were based around the Potomac in Vienna, Virginia, and on Saturday morning, they were sent out to search for signs of the assassins and learned Booth's identity as the assassin. A two-hour procession down Pennsylvania Avenue to the Capitol Building took place during Lincoln's funeral. Corbett and the rest of the Cavalry formed part of the parade, joining other regiments leading the hearse. Corbett's regiment had barely left the Capitol after the funeral parade when orders caught up with Canadian-born Lt. Edward P. Doherty to pursue a lead about Booth. Corbett took time to request permission to attend night meetings at McKendree Chapel, where the leader allowed Corbett to lead in prayer over the President's death. On April 24, the regiment was sent to capture Booth. Corbett was among the first to volunteer.[25] On April 26, the regiment surrounded Booth and one of his accomplices, David Herold, in a tobacco barn on the Virginia farm of Richard Garrett. Doherty asked Corbett "to deploy the men right and left" to surround the farm.[26] Corbett and other soldiers arrayed themselves around the barn to ensure neither man escaped. Herold surrendered, but Booth refused and cried out, "I will not be taken alive!". The barn was set on fire in an attempt to force him out into the open, but Booth remained inside.[27] Corbett was positioned near a large crack in the barn wall. He asked Doherty and offered to enter the barn and try to subdue Booth by himself; Corbett urged that if Booth shot him, the other soldiers could overwhelm him before he could reload (Corbett was unaware that Booth had a carbine and several revolvers.) Doherty rejected the suggestion, and Corbett moved back to his position. Lt. Colonel Everton Conger came past Corbett, igniting clumps of hay and slipped them in the cracks in the wall, hoping to burn Booth out. Booth walked to the flames, assessing whether he could extinguish the fire.[28] Corbett claimed that he saw Booth aim his carbine, prompting him to shoot at Booth through the crack with his Colt revolver, mortally wounding him. Booth screamed in pain and fell to the ground.[29]

"Finding the fire gaining upon him (Booth), he turned to the other side of the barn, and got toward where the door was, and as he got there I saw him make a movement toward the door. I supposed he was going to fight his way out. One of the men, who was watching him, told me that he aimed the carbine at me. He was taking aim with the carbine, but at whom I could not say. My mind was upon him attentively to see that he did no harm, and when I became impressed that it was time I shot him. I took steady aim on my arm, and shot him through a large crack in the barn."

Doherty, Conger, and several soldiers rushed into the burning barn and carried Booth out. Assessing his condition, Corbett and others felt a cosmic justice in that Booth's entry wound was in the same spot he shot Lincoln.[31][32][33] The bullet struck Booth in the back of the head behind his left ear and passed through his neck.[34][31] Three of Booth's vertebrae were pierced and his spinal cord was partially severed, leaving him completely paralyzed.[35][36] As Mary Clemmer Ames would later put it, "The balls entered the skull of each at nearly the same spot, but the trifling difference made an immeasurable difference...Mr. Lincoln was unconscious...Booth suffered as exquisite agony as if he had been broken on a wheel."[37] Conger initially thought Booth had shot himself, though Colonel Lafayette C. Baker was certain he had not. Corbett stepped forward and admitted he shot Booth, giving Doherty his gun.[31][38] Doherty, Baker and Conger questioned Corbett, who said he had intended to merely wound Booth in the shoulder but that either his aim slipped or Booth moved when Corbett fired. Initial statements by Doherty and others made no mention of Corbett having violated any orders, nor did they suggest that he would face disciplinary action for shooting Booth.[39] According to later sources, when asked why he had violated orders, Corbett replied, "Providence directed me."[40] Author Scott Martelle disputes this, noting "his initial statement, and those by Baker, Conger, and Doherty don't mention Providence...those details came long after the shooting itself, amid the swirl of rumor and conjecture and considerable lobbying over the reward money."

Dragged to the porch of Garrett's farmhouse, Booth asked for water.[39] Conger and Baker poured some into his mouth, which he immediately spat out, unable to swallow. Booth asked to be rolled over and turned facedown; Conger rejected the idea. "Then at least turn me on my side," Booth pleaded; the move did not relieve Booth's suffering. Baker said, "He seemed to suffer extreme pain whenever he was moved...and would several times repeat, 'Kill me!'"[41] At sunrise, Booth remained in agony, and his breathing became more labored and irregular. Unable to move his limbs, he asked a soldier to lift his hands to his face and uttered his last words as he gazed at them: "Useless ... useless." Booth then began gasping for air as his throat continued to swell, and he made a gurgling sound before he died from asphyxia, approximately two to three hours after Corbett shot him.

Doherty told Corbett to ride to neighboring farms to find breakfast for the men. Corbett did so, but first "rode off to a spot when I could be alone and pray, and when I had gone through my usual morning prayer, I asked the Lord in regard to the shooting. At once, I was filled with praise, for I felt a clear consciousness that it was an act of duty in the sight of God." Corbett found supplies for half the men, and they finished their meal before Booth died.[42] Conger and Corbett rode off to Washington.[43]

Fame

[edit]

According to Johnson, Corbett was accompanied by Lt. Doherty to the War Department in Washington, D.C. to meet Secretary Edwin Stanton about Booth's shooting. Edward Steers writes that it was "not against orders. Conger (said)..."They had no orders either to fire or not to fire."[44] Corbett maintained that he believed Booth had intended to shoot his way out of the barn and that he acted in self-defense. He told Stanton, "...Booth would have killed me if I had not shot first. I think I did right."[45] Corbett maintained that he did not intend to kill Booth but merely wanted to inflict a disabling wound, but either his aim slipped or Booth moved at the moment Corbett pulled the trigger.[39] Stanton paused and then stated, "The rebel is dead. The patriot lives; he has spared the country expense, continued excitement and trouble. Discharge the patriot."[45] Martelle says that "no other source mentions such a meeting...Johnson's memoir, which came out a half-century later, is just another part of the lore."[46] Corbett was greeted by a cheering crowd. As he made his way to Mathew Brady's studio to have his official portrait taken, the crowd followed him, asking for autographs and requesting that he tell them about shooting Booth. Corbett told the crowd:

I aimed at his body. I did not want to kill him....I think he stooped to pick up something just as I fired. That may probably account for his receiving the ball in the head. [W]hen the assassin lay at my feet, a wounded man, and I saw the bullet had taken effect about an inch back of the ear, and I remembered that Mr. Lincoln was wounded about the same part of the head, I said: "What a God we have...God avenged Abraham Lincoln."[32]

Corbett testified in the trial of the Lincoln assassination conspirators, testifying on May 17, 1865.[30]

Corbett was largely considered a hero by the public and press. Initial newspaper reporters described him as a simple and humble man devoted, possibly excessively, to his faith; he had eccentricities but also did his duty well.[46] One newspaper editor declared that Corbett would "live as one of the World's great avengers."[47] For his part in Booth's capture, Corbett received a portion of the $100,000 reward money, amounting to $1,653.84 (equivalent to $33,000 in 2023).[48][49] His annual salary as a U.S. sergeant was $204 (equivalent to $4,000 in 2023). Corbett received offers to purchase the gun he used to shoot Booth. He refused, stating, "That is not mine—it belongs to the Government, and I would not sell it for any price."[50] Corbett also declined an offer for one of Booth's pistols as he did not want a reminder of shooting Booth.[50]

Negative responses

[edit]Later, newspaper accounts began to offer some criticism of Corbett's actions, that he had acted wilfully and against orders when he shot Booth (no orders were issued on whether Booth should be taken alive).[43] Richard Garrett, the owner of the farm on which Booth died, and his 12-year-old son Robert said years later that Booth had never reached for his gun.[51] Steers disputes this, noting that this contradicts original accounts.

Post-war life

[edit]Southern sympathizers sent letters threatening to kill Corbett, so he kept a gun nearby at all times to defend himself.[52] After his discharge from the army in August 1865, Corbett returned to work as a milliner in Boston and frequently attended the Bromfield Street Church. When the hatting business in Boston slowed, Corbett moved to Danbury, Connecticut, to continue his work and also "preached in the country round about." By 1870, he had relocated once again to Camden, New Jersey, where he was known as a "Methodist lay preacher" while also continuing to be a milliner.[53] Corbett's inability to hold a job was attributed to his fanatical behavior; he was routinely fired after continuing his habit of stopping work to pray for his co-workers.[54] To earn money, Corbett capitalized on his role as "Lincoln's Avenger".[17] He gave lectures about the shooting of Booth accompanied by illustrated lantern slides at Sunday schools, women's groups and tent meetings. Corbett was never asked back due to his increasingly erratic behavior and incoherent speeches.[54]

R. B. Hoover, a man who later befriended Corbett, recalled that Corbett believed "men who were high in authority at Washington at the time of the assassination" were hounding him. Corbett said the men were angry because he had deprived them of prosecuting and executing John Wilkes Booth themselves. He also believed the same men had gotten him fired from various jobs.[55] Corbett's paranoia was furthered by hate mail he received for killing Booth. He became fearful that "Booth's Avengers" or organizations like the "Secret Order" were planning to seek revenge upon him and took to carrying a pistol with him at all times. As his paranoia increased, Corbett began brandishing his pistol at friends or strangers he deemed suspicious.[48]

While attending the Soldiers' Reunion of the Blue and Gray in Caldwell, Ohio, in 1875, Corbett got into an argument with several men over the death of John Wilkes Booth. The men questioned if Booth had been killed at all, which enraged Corbett. He then drew his pistol on the men but was removed from the reunion before he could fire it.[55] In 1878, Corbett moved to Concordia, Kansas, where he acquired a plot of land through homesteading upon which he constructed a dugout home. He continued working as a preacher and attended revival meetings frequently.[56] Throughout the rest of his life, he began to become paranoid that Booth's family or friends would come and kill him, causing him to go insane.[citation needed]

Disappearance

[edit]Due to his fame as "Lincoln's Avenger", Corbett was appointed assistant doorkeeper of the Kansas House of Representatives in Topeka in January 1887. On February 15, he became convinced that officers of the House were discriminating against him. He jumped to his feet, brandished a revolver, and began chasing the officers out of the building. No one was hurt, and Corbett was arrested. The following day, a judge declared Corbett insane and sent him to the Topeka Asylum for the Insane. On May 26, 1888, he escaped from the asylum on horseback.[57] He then rode to Neodesha, Kansas, where he briefly stayed with Richard Thatcher. When Corbett left, he told Thatcher he was going to Mexico.[56]

Conjecture arose that rather than going to Mexico, Corbett may have settled in a cabin he built in the forests near Hinckley, in Pine County in eastern Minnesota and that he died in the Great Hinckley Fire on September 1, 1894. This conjecture was based on speculation about the name "Thomas Corbett" appearing on the list of dead and a secondhand account by someone who said the fire victim had claimed to be Boston Corbett.[58][59] Scott Martelle cited it as "too tenuous a connection to credit."[60][a]

Impostors

[edit]Several men claimed to be him in the years following Corbett's disappearance. A few years after Corbett was last seen in Neodesha, Kansas, a patent medicine salesman in Enid, Oklahoma, filed an application using Corbett's name to receive pension benefits. After an investigation proved that the man was not Boston Corbett, he was imprisoned. In September 1905, a man arrested in Dallas also claimed to be Corbett. He, too, was proven to be an impostor and was sent to prison for perjury and then to the Government Hospital for the Insane.[62]

Legacy

[edit]Scott Martelle, who wrote the 2015 biography The Madman and the Assassin: The Strange Life of Boston Corbett, the Man Who Killed John Wilkes Booth, called Corbett "the closest to an average, everyday person...a regular, run-of-the-mill American—albeit a strange one—who did his job as a hatter, and then as a soldier".[60]

Memorials

[edit]In 1958, Boy Scout Troop 31 of Concordia, Kansas, built a roadside monument to Corbett on Key Road. A small sign was also placed to mark the dugout where Corbett had lived.[63]

Portrayals

[edit]A fictional version of Corbett appears in the novel Andersonville (1955). Dabbs Greer played a fictitious version of Corbett in the Lawman episode "The Unmasked" (1962), in which Corbett is living under the name "Joe Brockway" as a Wyoming hotel owner, being searched for by two former vengeful Confederate soldiers (although he gives his name as "Bill Corbett"). Corbett is portrayed by William Mark McCullough in the series Manhunt (2024).[b]

See also

[edit]- Edward P. Doherty

- Everton J. Conger

- Lafayette C. Baker

- List of people who disappeared

- Henry Rathbone, wounded by Booth during Lincoln's assassination; he was declared insane after killing his wife

Notes

[edit]- ^ Writer Dale L. Walker proposed Corbett as a suspect in the Jack the Ripper murders of 1888.[61]

- ^ Coincidentally, McCullough previously portrayed John Wilkes Booth in the documentary Lincoln's Last Day (2015).

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Jameson 2013, pp. 128

- ^ a b c Walker & Jakes 1998, p. 159

- ^ a b Johnson 1914, p. 45

- ^ Martelle 2015, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Walker & Jakes 1998, p. 160

- ^ Martelle 2015, p. 9.

- ^ Johnson 1914, pp. 45–46

- ^ Swanson 2007, p. 329

- ^ Martelle 2015, p. 10.

- ^ Harper's Weekly, May 13, 1865

- ^ Kauffman 2004, p. 310

- ^ Johnson 1914, p. 46

- ^ Martelle 2015, p. 11.

- ^ Martelle 2015, p. 13.

- ^ Martelle 2015, p. 22.

- ^ Walker & Jakes 1998, pp. 160–161

- ^ a b c Walker & Jakes 1998, p. 161

- ^ Jameson 2013, p. 129

- ^ Martelle 2015, p. 38.

- ^ Martelle 2015, p. 42.

- ^ Martelle 2015, p. 50.

- ^ John McElroy (1897). Andersonville: A Story of Rebel Military Prisons. Vol. 4. Toledo: D. R. Locke. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ Chamlee & Chamlee 1989, p. 289

- ^ Chipman 1891, p. 40

- ^ Martelle 2015, p. 98.

- ^ Martelle 2015, p. 101.

- ^ Swanson 2007, pp. 324–335

- ^ Martelle 2015, p. 102.

- ^ Terry Alford, Fortune's Fool: The Life of John Wilkes Booth.

- ^ a b Steers Jr., Edward (2010). "The Gay Lincoln Myth". The Trial: The Assassination of President Lincoln. University Press of Kentucky. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-8131-7275-0.

- ^ a b c Martelle 2015, p. 103.

- ^ a b Goodrich 2005, pp. 227–228

- ^ "The Death of John Wilkes Booth, 1865". Eyewitness to History/Ibis Communications. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

the bullet struck Booth in the back of the head, about an inch below the spot where his shot had entered the head of Mr. Lincoln.

- ^ "American Experience | The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln". PBS. Retrieved December 14, 2012.

- ^ Goodrich, p. 211.

- ^ Smith, pp. 210–213.

- ^ Clemmer, Mary. Ten Years in Washington: Life and Scenes in the National Capital as a Woman Sees Them. Cincinnati: Queen City Publishing Company, 1874.

- ^ Jameson 2013, p. 135

- ^ a b c Martelle 2015, p. 104.

- ^ Swanson 2007, p. 340

- ^ Swanson, p. 139.

- ^ Martelle 2015, p. 105.

- ^ a b Martelle 2015, p. 106.

- ^ Steers, Edward (2005). Blood on the Moon: The Assassination of Abraham Lincoln. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 104–105. ISBN 0-813-19151-3.

- ^ a b Goodrich 2005, p. 227

- ^ a b Martelle 2015, p. 110.

- ^ Goodrich 2005, p. 228

- ^ a b Goodrich 2005, p. 291

- ^ Swanson 2007, p. 358

- ^ a b Basler 1965, pp. 57–58

- ^ Nottingham 1997, p. 148

- ^ Martelle 2015, p. 118.

- ^ "Thomas P. 'Boston' Corbett". January 12, 2023. Retrieved June 9, 2024., CamdenHistory.com

- ^ a b Frazier, Robert B. (January 3, 1967). "The Strange Fate Of Boston Corbett". Eugene Register-Guard. p. 5. Retrieved November 22, 2014.

- ^ a b Sparks et al. 1889, p. 382

- ^ a b Johnson 1914, p. 51

- ^ Walker, Dale (September 2005). "The Mad Hatter". American Cowboy. 12 (3): 82. ISSN 1079-3690. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

- ^ Lincoln Herald, Volume 86, Lincoln Memorial University Press., 1984, pp. 152–155

- ^ Kubicek, Earl C, "The Case of the Mad Hatter", Lincoln Herald, Volume 83, Lincoln Memorial University Press, 1981, pp. 708–719

- ^ a b Martelle 2015, p. 189.

- ^ Dale L. Walker (November 15, 1998). Legends and Lies: Great Mysteries of the American West. Tom Doherty Associates. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-312-86848-2.

- ^ Johnson 1914, pp. 52–53

- ^ "He Killed Lincoln's Killer, Then Lived In a Hole". Roadside America. Retrieved October 10, 2008.

Sources

[edit]- Basler, Roy (1965). The Assassination and History of the Conspiracy. New York: Hobbs, Dorman & Company, INC. ISBN 978-1-432-80265-3.

- Chamlee, Roy Z.; Chamlee, Roy Z. Jr. (1989). Lincoln's Assassins: A Complete Account of Their Capture, Trial, and Punishment. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-89950-420-9.

- Chipman, Norton Parker (1891). The Horrors of Andersonville Rebel Prison: Trial of Henry Wirz, the Andersonville Jailer; Jefferson Davis' Defense of Andersonville Prison Fully Refuted. Bancroft Co.

- Goodrich, Thomas (2005). The Darkest Dawn: Lincoln, Booth, and the Great American Tragedy. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-11132-6.

- Jameson, W. C. (2013). John Wilkes Booth: Beyond the Grave. Taylor Trade Publishing. ISBN 978-1-589-79832-8.

- Johnson, Byron Berkeley (1914). Abraham Lincoln and Boston Corbett: With Personal Recollections of Each; John Wilkes Booth and Jefferson Davis, a True Story of Their Capture. B. B. Johnson.

- Kauffman, Michael W. (2004). American Brutus: John Wilkes Booth and the Lincoln Conspiracies. Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-50785-4.

- Martelle, Scott (2015). The Madman and the Assassin: The Strange Life of Boston Corbett, the Man Who Killed John Wilkes Booth. Chicago: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 9781613730188.

- Nottingham, Theodore J. (1997). The Curse of Cain: The Untold Story of John Wilkes Booth. Theosis Books. ISBN 978-1-580-06021-9.

- Sparks, Jared; Everett, Edward; Lowell, James Russell; Lodge, Henry Cabot (1889). The North American Review, Volume 149. Making of America Project. University of Northern Iowa.

- Swanson, James L. (2007). Manhunt: The 12-Day Chase for Lincoln's Killer. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-051850-9.

- Walker, Dale L.; Jakes, John (1998). Legends and Lies: Great Mysteries of the American West. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-86848-2.

External links

[edit]- 1832 births

- 1880s missing person cases

- 19th-century Methodists

- American Civil War prisoners of war held by the Confederate States of America

- American escapees

- American prisoners sentenced to death

- Methodists from Massachusetts

- Castrated people

- Converts to Methodism

- English emigrants to the United States

- American milliners

- Members of the Methodist Episcopal Church

- Methodist evangelists

- Military personnel from London

- Military personnel from Troy, New York

- Missing person cases in Minnesota

- People associated with the assassination of Abraham Lincoln

- People declared dead in absentia

- Military personnel from Boston

- People from Camden, New Jersey

- People from Concordia, Kansas

- People from Hinckley, Minnesota

- People from Noble County, Ohio

- People of New York (state) in the American Civil War

- People with schizophrenia

- Union army soldiers

- United States Army personnel who were court-martialed

- Prisoners sentenced to death by the United States military