Bessie Coleman

Bessie Coleman | |

|---|---|

Coleman in 1923 | |

| Born | January 26, 1892 Atlanta, Texas, U.S. |

| Died | April 30, 1926 (aged 34) Jacksonville, Florida, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Plane crash |

| Burial place | Lincoln Cemetery, Cook County, Illinois |

| Known for | First African-American and Native American female aviator |

| Spouse | |

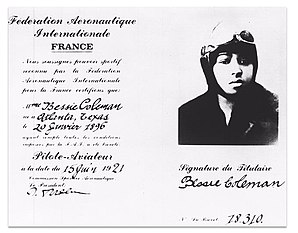

Elizabeth Coleman (January 26, 1892 – April 30, 1926)[2] was an early American civil aviator. She was the first African-American woman and first Native American to hold a pilot license,[3][4][5][6][7][8][9] and is the earliest known Black person to earn an international pilot's license.[10] She earned her license from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale on June 15, 1921.[5][6][11]

Born to a family of sharecroppers in Texas, Coleman worked in the cotton fields at a young age while also studying in a small segregated school. She attended one term of college at Langston University. Coleman developed an early interest in flying, but African Americans, Native Americans, and women had no flight training opportunities in the United States, so she saved and obtained sponsorships in Chicago to go to France for flight school.

She then became a high-profile pilot in notoriously dangerous air shows in the United States. She was popularly known as "Queen Bess" and "Brave Bessie",[12] and hoped to start a school for African-American fliers. Coleman died in a plane crash in 1926. Her pioneering role was an inspiration to early pilots and to the African-American and Native American communities.

Early life

Coleman[13] was born on January 26, 1892, in Atlanta, Texas,[10] the tenth of 13 children of George Coleman, an African American who may have had Cherokee or Choctaw grandparents, and Susan Coleman, who was African American.[14][15] Nine of the children survived childhood, which was typical for the time.[14] When Coleman was two years old, her family moved to Waxahachie, Texas, where they lived as sharecroppers.[15] Coleman began attending school in Waxahachie at the age of six. She walked four miles each day to her segregated, one-room school, where she loved to read and established herself as an outstanding math student.[15] She completed her elementary education in that school.[15]

Every season, Coleman's routine of school, chores, and church was interrupted for her to participate in bringing in the cotton harvest. In 1901, George Coleman left his family. He moved to Oklahoma, or Indian Territory, as it was then called, to find better opportunities, but his wife and children did not follow. At the age of 12, Coleman was accepted into the Missionary Baptist Church School on scholarship. When she turned eighteen, she took her savings and enrolled in the Oklahoma Colored Agricultural and Normal University in Langston, Oklahoma (now called Langston University). She completed one term before her money ran out and she returned home.[16]

Career

Chicago

In 1915, at the age of 23, Coleman moved to Chicago, Illinois, where she lived with her brothers. In Chicago, she worked as a manicurist at the White Sox Barber Shop, where she heard stories of flying during wartime from pilots returning home from World War I. She took a second job as a restaurant manager of a chili parlor to save money in hopes of becoming a pilot herself.[17] American flight schools of the time admitted neither women nor black people, so Robert S. Abbott, founder and publisher of the Chicago Defender newspaper, encouraged her to study abroad.[4] Abbot publicized Coleman's quest in his newspaper and she received financial sponsorship from banker Jesse Binga and the Defender.[17]

France

Bessie Coleman took a French-language class at the Berlitz Language Schools in Chicago and then traveled to Paris, France, on November 20, 1920, so that she could earn her pilot license. She learned to fly in a Nieuport 564 biplane with "a steering system that consisted of a vertical stick the thickness of a baseball bat in front of the pilot and a rudder bar under the pilot's feet."[18]

On June 15, 1921, Coleman became the first black woman[10] and first Native American[19] to earn an aviation pilot's license and the first black person[10] and first self-identified Native American[19] to earn an international aviation license from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale.[10] She was also the first American of any race or gender to be awarded these credentials directly from the FAI, as opposed to applying through the National Aeronautic Association.[20] Determined to polish her skills, Coleman spent the next two months taking lessons from a French ace pilot near Paris and, in September 1921, she sailed for America. She became a media sensation when she returned to the United States.

Airshows

The air is the only place free from prejudices. I knew we had no aviators, neither men nor women, and I knew the Race needed to be represented along this most important line, so I thought it my duty to risk my life to learn aviation...

With the age of commercial flight still a decade or more in the future, Coleman quickly realized that in order to make a living as a civilian aviator she would have to become a "barnstorming" stunt flier, performing dangerous tricks in the air with the then-still-novel technology of airplanes for paying audiences. But, to succeed in this highly competitive arena, she would need advanced lessons and a more extensive repertoire. Returning to Chicago, she could not find anyone willing to teach her, so in February 1922, she sailed again for Europe.[18]

Coleman spent the next two months in France completing an advanced course in aviation. She then left for the Netherlands to meet with Anthony Fokker, one of the world's most distinguished aircraft designers. She also traveled to Germany, where she visited the Fokker Corporation and received additional training from one of the company's chief pilots. She then returned to the United States to launch her career in exhibition flying.[18]

"Queen Bess", as she was known, was a highly popular draw for the next five years. Invited to important events and often interviewed by newspapers, she was admired by both blacks and whites. She primarily flew Curtiss JN-4 Jenny biplanes and other aircraft that had been army surplus aircraft left over from the war. She made her first appearance in an American airshow on September 3, 1922, at an event honoring veterans of the all-black 369th Infantry Regiment of World War I. Held at Curtiss Field on Long Island near New York City, and sponsored by her friend Abbott and the Chicago Defender newspaper, the show billed Coleman as "the world's greatest woman flier"[22] and featured aerial displays by eight other American ace pilots, and a jump by black parachutist Hubert Julian.[23]

Six weeks later, Coleman returned to Chicago, performing in an air show, this time to honor World War I's 370th Infantry Regiment. She delivered a stunning demonstration of daredevil maneuvers – including figure eights, loops, and near-ground dips to a large and enthusiastic crowd at the Checkerboard Airdrome – now the grounds of Hines Veterans Administration Medical Center, Hines, Illinois, Loyola Hospital, Maywood, and nearby Cook County Forest Preserve.[24]

The thrill of stunt flying and the admiration of cheering crowds were only part of Coleman's dream. Coleman never lost sight of her childhood vow to one day "amount to something". As a professional aviator, Coleman often would be criticized by the press for her opportunistic nature and the flamboyant style she brought to her exhibition flying. She also quickly gained a reputation as a skilled and daring pilot who would stop at nothing to complete a difficult stunt. In Los Angeles, she broke a leg and three ribs when her plane stalled and crashed on February 22, 1923.[12]

Committed to promoting aviation and combating racism, Coleman spoke to audiences across the country about the pursuit of aviation and goals for African Americans. She absolutely refused to participate in aviation events that prohibited the attendance of African Americans.[25]

In the 1920s, she met the Rev. Hezakiah Hill and his wife Viola on a speaking tour in Orlando, Florida. The community activists invited her to stay with them at the parsonage of Mount Zion Missionary Baptist Church on Washington Street in the neighborhood of Parramore. A local street was renamed "Bessie Coleman" Street in her honor in 2013. The couple, who treated her as a daughter, persuaded her to stay, and Coleman opened a beauty shop in Orlando to earn extra money to buy her own plane.[26]

Through her media contacts, she was offered a role in a feature-length film titled Shadow and Sunshine, to be financed by the African American Seminole Film Producing Company. She gladly accepted, hoping the publicity would help to advance her career and provide her with some of the money she needed to establish her own flying school. But upon learning that the first scene in the movie required her to appear in tattered clothes, with a walking-stick and a pack on her back, she refused to proceed. "Clearly ... [Bessie's] walking off the movie set was a statement of principle. Opportunist though she was about her career, she was never an opportunist about race. She had no intention of perpetuating the derogatory image most whites had of most blacks," wrote Doris Rich.[18]

It's tempting to draw parallels between me and Ms. Coleman . . .[but] I point to Bessie Coleman and say here is a woman, a being, who exemplifies and serves as a model for all humanity, the very definition of strength, dignity, courage, integrity, and beauty.

Legacy

Coleman would not live long enough to establish a school for young black aviators, but her pioneering achievements served as an inspiration for a generation of African-American men and women. "Because of Bessie Coleman," wrote Lieutenant William J. Powell in Black Wings (1934), dedicated to Coleman, "we have overcome that which was worse than racial barriers. We have overcome the barriers within ourselves and dared to dream."[28] Powell served in a segregated unit during World War I, and tirelessly promoted the cause of black aviation through his book, his journals, and the Bessie Coleman Aero Club, which he founded in 1929.[29][18]

Coleman's example proved an inspiration for a number of pioneers in aeronautics and eventually astronautics, including John Robinson, Cornelius Coffey, Willa Brown, Janet Harmon Bragg, Robert H. Lawrence Jr., and Mae Jemison.[30]

Death

On April 30, 1926, Coleman was in Jacksonville, Florida. She had recently purchased a Curtiss JN-4 (Jenny) in Dallas. Her mechanic and publicity agent, 24-year-old William D. Wills, flew the plane from Dallas in preparation for an airshow and had to make three forced landings along the way because the plane had been so poorly maintained.[31] Upon learning this, Coleman's friends and family did not consider the aircraft safe and implored her not to fly it, but she refused. On take-off, Wills was flying the plane with Coleman in the other seat. She was planning a parachute jump for the next day and was unharnessed as she needed to look over the side to examine the terrain.[13]

About ten minutes into the flight, the plane unexpectedly went into a dive and then a spin at 3,000 feet above the ground. Coleman was thrown from the plane at 2,000 ft (610 m), and was killed instantly when she hit the ground. Wills was unable to regain control of the plane, and it plummeted to the ground. He died upon impact. The plane exploded, bursting into flames. Although the wreckage of the plane was badly burned, it was later discovered that a wrench used to service the engine had jammed the controls. Coleman was 34 years old.[18]

Funeral services were held in Florida, before her body was sent back to Chicago. While there was little mention in most media, news of her death was widely carried in the African-American press. Ten thousand mourners attended her ceremonies in Chicago, which were led by activist Ida B. Wells.[13]

Honors

- Atlanta, Texas, has a Regional History Museum which displays a downscale reproduction version of Bessie Coleman's yellow bi-plane "Queen Bess." The museum display also includes a uniform and other memorabilia regarding the life and times of Bessie Coleman. Outside the regional history museum is a Texas Historical Marker located at 101 N. East Street in Historic Downtown, Atlanta. The road to the Hall-Miller Municipal Airport in Atlanta is named Bessie Coleman Drive in her honor.

- A public library in Chicago was named in Coleman's honor in 1993.[32]

- A memorial plaque has been placed by the Chicago Cultural Center at the location of her former home, 41st and King Drive in Chicago, and it is a tradition for African-American aviators to drop flowers during flyovers of her grave at Lincoln Cemetery.[33]

- Roads at O'Hare International Airport in Chicago,[34] Oakland International Airport in California,[35] Tampa International Airport in Florida,[36] and at Germany's Frankfurt International Airport are named for her.[37] A roundabout leading to Nice Airport in the South of France was named after Coleman in March 2016, and there are streets in Poitiers, and the 20th Arrondissement of Paris also named after her.[38][39]

- Bessie Coleman Middle School in Cedar Hill, Texas, is named for her.

- Bessie Coleman Boulevard in Waxahachie, Texas, where she lived as a child is named in her honor.[40]

- B. Coleman Aviation, a fixed-base operator based at Gary/Chicago International Airport, is named in her honor.[41]

- Several Bessie Coleman Scholarship Awards have been established for high school seniors planning careers in aviation.

- The U.S. Postal Service issued a 32-cent stamp honoring Coleman in 1995.[42][43] The Bessie Coleman Commemorative is the 18th in the U.S. Postal Service Black Heritage series.

- In 2001, Coleman was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.[44]

- In 2006, Coleman was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame.[45]

- In 2012, a bronze plaque with Coleman's likeness was installed on the front doors of Paxon School for Advanced Studies located on the site of the Jacksonville airfield where Coleman's fatal flight took off.[46]

- Coleman was honored with a toy character in season 5, episode 11a of the children's animated television program Doc McStuffins.

- Coleman was placed No. 14 on Flying's 2013 list of the "51 Heroes of Aviation".[47]

- In 2014, Coleman was inducted into the International Air & Space Hall of Fame at the San Diego Air & Space Museum.[48]

- On January 25, 2015, Orlando renamed West Washington Street to recognize the street's most accomplished resident.[26]

- On January 26, 2017,[49] the 125th anniversary of her birth, a Google Doodle was posted in her honor.[50]

- In December 2019, The New York Times featured Coleman in their Overlooked (obituary feature): "Bessie Coleman, Pioneering African-American Aviatrix"[13]

- In 2021, when Juneteenth became a federal holiday, a flyover was held in Colorado to honor both her and the new holiday.[51]

- In 2021, the International Astronomical Union named a mountain (and possible volcano) on Pluto, Coleman Mons, in her honor. It is located on the edge of the heart-shaped Tombaugh Regio.[52][53]

- To commemorate the 100th anniversary of Coleman earning her flying license, in August 2022, American Airlines flew a commemorative flight from "Dallas-Fort Worth to Phoenix. The flight was operated by an all-Black Female crew — from the pilots and Flight Attendants to the Cargo team members and the aviation maintenance technician."[54][55]

- Coleman was honored on an American Women quarter in 2023.[56]

- Bessie Coleman Elementary School in Corvallis, Oregon, is named after her.[57]

- In 2023, Mattel added a Bessie Coleman Barbie doll to its "Inspiring Women" series.[58]

- In 2023, The Flight, a play inspired by Bessie Coleman, debuted at the Factory Theatre, written and starring Beryl Bain.[59]

See also

- List of firsts in aviation

- Eugene Bullard, the first African-American to earn a pilot's license

- Leah Hing, first Chinese American woman to earn a pilot's license

- Mae Jemison, the first African-American female astronaut in space; she carried a picture of Bessie Coleman with her on her first mission

- Military history of African Americans

- Azellia White, the first African-American woman to earn a pilot's license in Texas

References

Citations

- ^ Roni Morales (November 1, 2014). "Bessie Coleman – Aviator". Rootsweb. Retrieved December 17, 2017.

- ^ "Bessie Coleman | American aviator". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ^ "O'Hare display honors 1st African American, Native American to earn international pilot's license". abc7chicago.com. July 30, 2021. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ a b "Bessie Coleman (1892–1926)". PBS.org. Archived from the original on March 26, 2017. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

- ^ a b "Some Notable Women In Aviation History". Women in Aviation International. Archived from the original on June 29, 2016. Retrieved April 10, 2008.

- ^ a b Onkst, David H. (2016). "Women in History: Bessie Coleman". Natural Resources Conservation Service Nevada. Archived from the original on February 16, 2016. Retrieved January 5, 2016.

- ^ "Fighter pilot takes inspiration to new heights". U.S. Air Force. March 28, 2018. Retrieved July 14, 2019.

- ^ "Indigenous Connections and Collections Library Blog – Bessie Coleman Aerospace Legacy". Indian Pueblo Cultural Center. November 7, 2022. Retrieved February 2, 2024.

- ^ Alexander, Kerri Lee (2022). "Bessie Coleman (1892–1926)". National Women's History Museum. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Bix, Amy Sue (2005). "Bessie Coleman: Race and Gender Realities Behind Aviation Dreams". In Dawson, Virginia Parker; Bowles, Mark D. (eds.). Realizing the Dream of Flight: Biographical Essays in Honor of the Centennial of Flight, 1903–2003. NASA. pp. ix, 5. OCLC 60826554.

- ^ "Pioneer Hall of Fame". Women in Aviation International. Archived from the original on March 27, 2008. Retrieved April 10, 2008.

- ^ a b "Bessie Coleman". National Women's History Museum. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Slotnik, Daniel E. (December 11, 2019). "Overlooked No More: Bessie Coleman, Pioneering African-American Aviatrix". The New York Times. Retrieved May 30, 2022.

- ^ a b Ganson, Barbara (2014). Texas Takes Wing: A Century of Flight in the Lone Star State. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-292-75408-9.

- ^ a b c d Marck, Bernard (2009). Women Aviators: From Amelia Earhart to Sally Ride, Making History in Air and Space. Rizzoli International Publications. p. 67. ISBN 9782080301086.

- ^ Morales, Roni (February 25, 2020). "Coleman, Bessie". The Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State History Association. Archived from the original on December 24, 2011. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

Upon graduation from high school, she enrolled at the Colored Agricultural and Normal University (now Langston University) in Langston, Oklahoma. Financial difficulties, however, forced her to quit after one semester because she could not afford to attend another one.

- ^ a b Creasman 1997, p. 159.

- ^ a b c d e f Rich, Doris (1993). Queen Bess: Daredevil Aviator. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press. pp. 37, 47, 57, 109–111, 145. ISBN 1-56098-265-9.

- ^ a b Kerri Lee Alexander (2018). "Bessie Coleman". National Women's History Museum. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- ^ Mathias, Marisa. "Bessie Coleman". National Women's History Museum. Retrieved January 3, 2025.

- ^ "Bessie Coleman". Black History pages (BHP). Archived from the original on January 28, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Toth, Maria Lynn (February 10, 2001). "Daredevil of the Sky: The Bessie Coleman Story". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 5, 2012. Retrieved February 24, 2011.

- ^ "Negress Pilots Airplane: Bessie Coleman Makes Three Flights for Fifteenth Infantry". The New York Times. September 4, 1922. p. 9. Retrieved May 30, 2022 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Keating, Ann Durkin (2005). "Bessie Coleman: Pioneer Chicago Aviator". Encyclopedia of Chicago. Retrieved February 28, 2017.

- ^ Creasman 1997, p. 162.

- ^ a b Hudak, Stephen (January 31, 2015). "Orlando renames street in honor of black 'daredevil aviatrix'". Orlando Sentinel.

- ^ Creasman 1997, p. 163.

- ^ Powell, William J. (1934). Black Wings. Los Angeles: Ivan Deach, Jr. OCLC 3261929.

- ^ Broadnax, Samuel L. (2007). Blue Skies, Black Wings: African American Pioneers of Aviation. Westport, CT: Praeger. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-275-99195-1.

- ^ Nettles, Arionne (December 14, 2023). "The first Black-owned airport in the U.S. was in Robbins, Illinois". WBEZ. Retrieved December 15, 2023.

- ^ "Bessie Coleman Facts". yourdictionary.com. Archived from the original on January 5, 2014. Retrieved November 15, 2013.

- ^ "About Coleman Branch". Chicago Public Library. Retrieved February 28, 2017.

- ^ "Markers of Distinction: Bessie Coleman". Chicago Tribute. City of Chicago, Chicago Cultural Center. Archived from the original on February 14, 2016. Retrieved March 27, 2015.

- ^ "Bessie Coleman Drive, Chicago". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ^ "Bessie Coleman Drive, Alameda". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ^ "Bessie Coleman Boulevard, Tampa". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ^ "Bessie-Coleman-Straße, Frankfurt". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ^ "Rue Bessie Coleman, Poitiers". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ^ "Rue Bessie Coleman, Paris". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ^ "Bessie Coleman Boulevard, Waxahachie". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ^ "About". B. Coleman Aviation. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- ^ "Stamp Series". United States Postal Service. Archived from the original on August 10, 2013. Retrieved September 9, 2013.

- ^ Sine, Richard L.; Galpin, Jonathan. "Bessie Coleman". US Stamp Gallery.com. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ^ "Bessie Coleman", National Women's Hall of Fame.

- ^ "Coleman, Bessie". National Aviation Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on November 30, 2016. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ^ Soergel, Matt (October 28, 2013). "Looking to honor the daring 'Queen Bess'". The Florida Times-Union. p. A-4.

- ^ "51 Heroes of Aviation". Flying. July 24, 2013.

- ^ Sprekelmeyer, Linda, editor. These We Honor: The International Aerospace Hall of Fame. Donning Co. Publishers, 2006. ISBN 978-1-57864-397-4.

- ^ "Bessie Coleman's 125th Birthday", google.com, retrieved January 25, 2023

- ^ "Who was Bessie Coleman and why does she still matter?". AlJazeera. January 26, 2017.

- ^ Bekiempis, Victoria (June 19, 2021). "US comes together to mark Juneteenth after recognizing it as federal holiday". The Guardian. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- ^ JHUAPL. "Great Exploration Revisited: New Horizons at Pluto and Charon". New Horizons. Archived from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ^ Talbert, Tricia (October 25, 2021). "Pluto Landmarks Named for Aviation Pioneers Ride and Coleman". NASA. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ^ "Empowering Women in the Skies". American Airlines News. August 19, 2022.

- ^ Van Cleave, Kris (August 17, 2022). "Bessie Coleman, first African American woman to earn a pilot's license, honored by All-Black, female airline crew". CBS News.

- ^ "United States Mint Announces 2023 American Women Quarters™ Program Honorees". U.S. Mint. March 30, 2022. Retrieved March 31, 2022.

- ^ "What's in a School Rename: Life, Legacy of Bessie Coleman". The Corvallis Advocate. April 16, 2022. Retrieved September 7, 2022.

- ^ "Bessie Coleman, pioneering pilot, now has her own Barbie". MSN. January 24, 2023. Retrieved February 2, 2023.

- ^ Wild, Stephi (January 24, 2023). "World Premiere of THE FLIGHT Comes to Factory Theatre". BroadwayWorld.com. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

Works cited

- Creasman, Kim (1997). "Black Birds in the Sky: The Legacies of Bessie Coleman and Dr. Mae Jemison". The Journal of Negro History. 82 (1): 159–163. doi:10.2307/2717501. ISSN 0022-2992. JSTOR 2717501. S2CID 141029557.

Further reading

- King, Anita (1976). "Brave Bessie: First Black Pilot". Essence Magazine. Parts 1 & 2 (May, June).

- Bilstein, Roger (1985). Aviation in Texas. Austin: Texas Monthly Press. ISBN 9780932012951.

- Freydberg, Elizabeth Hadley (1994). Bessie Coleman: The Brownskin Lady Bird. Garland. ISBN 9780815314615.

- Fisher, Lillian M. (1995). Brave Bessie: Flying Free. Hencrick-Long. ISBN 9780937460948.

- Hart, Philip S. (1996). Up in the Air: The Story of Bessie Coleman. Trailblazer Biographies. First Avenue Editions. ISBN 978-0876149782.

- Johnson, Dolores (1997). She Dared to Fly: Bessie Coleman. New York: Benchmark Books. ISBN 978-0761404873.

- Plantz, Connie (2001). Bessie Coleman: First Black Woman Pilot. African-American Biographies. Enslow Publishers. ASIN B01K3N5GUM.

- Holway, John R. (2012). Bessie Coleman: Pioneering Black Woman Aviator. ISBN 9780985738914.

External links

- Spivey, Lynne. "Bessie Coleman". bessiecoleman.com. Atlanta Historical Museum.

- "Bessie Coleman". Historical Marker Database (HMdb). Texas Historical Commission. 2002. Archived from the original on September 27, 2016. 33°6.848′N 94°9.931′W / 33.114133°N 94.165517°W

- Video:

- 1892 births

- 1926 deaths

- 20th-century African-American people

- 20th-century African-American women

- 20th-century American people

- Accidental deaths in Florida

- African-American aviators

- African-American women aviators

- American women aviators

- Aviation history of the United States

- American aviation pioneers

- Aviators from Texas

- Aviators killed in aviation accidents or incidents in the United States

- Barnstormers

- Deaths by falling out of an aircraft

- National Aviation Hall of Fame inductees

- People from Atlanta, Texas

- People from Chicago

- Victims of aviation accidents or incidents in 1926

- Wing walkers

- Langston University alumni