Robot (Doctor Who)

| 075 – Robot | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Doctor Who serial | |||

| Cast | |||

Others

| |||

| Production | |||

| Directed by | Christopher Barry | ||

| Written by | Terrance Dicks | ||

| Script editor | Robert Holmes | ||

| Produced by | Barry Letts | ||

| Music by | Dudley Simpson | ||

| Production code | 4A | ||

| Series | Season 12 | ||

| Running time | 4 episodes, 25 minutes each | ||

| First broadcast | 28 December 1974 | ||

| Last broadcast | 18 January 1975 | ||

| Chronology | |||

| |||

Robot is the first serial of the 12th season in the British science fiction television series Doctor Who, which was first broadcast in four weekly parts on BBC1 from 28 December 1974 to 18 January 1975. It was the first full serial to feature Tom Baker as the Fourth Doctor, as well as Ian Marter as new companion Harry Sullivan. In the serial, the director of an English research institute plots to use an experimental robot to steal nuclear launch codes and blackmail the world's governments with them.

The serial brought a full end to the Pertwee era, as it was the final story with the production team of Barry Letts and script editor Terrance Dicks. It was also the final regular appearance of UNIT, who had become regulars starting with the first Jon Pertwee serial Spearhead From Space.

The episode received mixed reviews from critics, seeing praise for the acting, especially that of Baker and Marter, but criticisms due to stereotypical villains and a weak plot.

Plot

[edit]Following his regeneration, the Fourth Doctor becomes delirious and erratic. The Doctor tries to sneak off in his TARDIS, but the Brigadier and Sarah Jane stop him, convincing him to help in finding the culprit in the theft of top secret plans for a disintegrator gun.

Sarah investigates the National Institute for Advanced Scientific Research, colloquially known as the "Think Tank". She finds that director Hilda Winters, her assistant Arnold Jellicoe, and Professor J.P. Kettlewell are developing a robot, K1, to be used to perform tasks in hazardous locations. Winters and Jellicoe have secretly instructed K1 to kill Cabinet Minister Joseph Chambers, and use a completed disintegrator gun to steal international nuclear launch codes from Chambers' safe. K1 discovers Sarah's presence, and Winters orders K1 to kill her. When UNIT arrives, the three conspirators and K1 escape with Sarah as their hostage.

Winters sends a list of demands to the world governments and gives them thirty minutes to comply, then orders Kettlewell to connect to the launch computers. Kettlewell, who never expected their plan to get to this stage, hesitates, and in the ensuing discussion, Sarah and Harry attempt to escape with Kettlewell's assistance. Winters orders K1 to stop them, but the robot inadvertently fires the disintegrator gun at Kettlewell, killing him. In a confused state due to the death of its creator, K1 falls to the ground and apparently shuts down.

As UNIT forces take Winters and Jellicoe away, K1 reactivates and attacks UNIT. K1 seeks out Sarah to protect her, a result of an Oedipus complex it developed from Sarah's previous compassion, according to the Doctor. The Doctor finds out about the living metal that Kettlewell used in constructing K1 and the metal virus he designed to reduce the world's metallic waste. He races back to Kettlewell's lab to synthesise a batch of the virus.The Brigadier fires the disintegrator gun at the robot, but the blast is absorbed by the living metal- and K1 grows to an enormous size. The Doctor returns, throwing a bucket of virus solution onto K1; the robot slowly shrinks before the virus consumes it. As they regroup back at UNIT headquarters, Sarah is saddened by the loss of K1. The Doctor offers to cheer her up with a trip in the TARDIS, extending the invitation to Harry as well.

Production

[edit]

As the Doctor was transitioning from the third to the fourth incarnations, changes were also occurring in the production department of Doctor Who. Barry Letts, who had been the producer since the second Jon Pertwee serial in 1970, was leaving the series, but would stay on to cast the part of the new Doctor as well as produce this debut serial. Letts would be succeeded for the next story by Philip Hinchcliffe, who trailed him on this story.

Terrance Dicks, who had worked on the series as a script editor since 1968,[1] was also leaving, to be replaced by Robert Holmes. Holmes had been a writer for the show since season six and penned four stories in Pertwee's era, including Spearhead from Space (1970), the Third Doctor's first serial. Though Dicks was leaving as script editor, he would still be involved with the series as an occasional writer. Having previously helped write the serials The Seeds of Death and The War Games (both 1969), Dicks would write the first story for the incoming Fourth Doctor.

The K1 robot costume was designed by one of the series' regular costume designers at the time, James Acheson, and built by sculptor[2] Allister Bowtell.[3]

Conception and writing

[edit]Terrance Dicks stated that a major influence for this story was King Kong (1933).[4] The initial script was written before Tom Baker had been cast as the Fourth Doctor, and there was some discussion of returning to an older actor. This would have required a younger character to handle the action scenes, so the character of Harry Sullivan was created. This was Sullivan's debut story, but he had been mentioned in the final episode of the preceding serial, when the Brigadier telephoned him, requesting medical help for the Doctor.

Dicks included a number of elements from Spearhead from Space: the Doctor being disorientated after regeneration, going to hospital to recover, changing costume as a result of escaping from hospital in a hospital gown, viewing himself in a mirror to see his new face, and storing the TARDIS key in his shoe.[5] These elements helped the audience with the transition between actors.[3][6][7]

Casting

[edit]

It was known beforehand that Jon Pertwee would be leaving his role as the Third Doctor and that a new Fourth Doctor would need to be cast for the part.[8] Tom Baker had previously had major parts in several films, including Nicholas and Alexandra (1971) and The Vault of Horror (1973), but had found himself unemployed as an actor and working in construction at the time.[9][10] He had written to Bill Slater, the Head of Serials at the BBC, asking for work.[10] Slater suggested Baker to Doctor Who producer Barry Letts, who had been looking to fill the part.[9][10] Letts saw Baker's work in The Golden Voyage of Sinbad (1973) and hired him.[11] Baker would continue in his role as the Doctor for seven seasons, longer than any other actor.[12]

Nicholas Courtney and John Levene reprised their roles as Brigadier Lethbridge-Stewart and Sergeant Benton respectively.[13] Levene had started his role with the Second Doctor story The Invasion (1968) as a member of the military organisation UNIT (the United Nations Intelligence Taskforce). Courtney started earlier in the same year in The Web of Fear, with his character's rank being a colonel. They, along with Sladen, would be the transition cast to carry through from the Third Doctor to the Fourth Doctor, though this would be the only UNIT story for the twelfth season. The Earth-based stories involving UNIT, which had regularly featured in the Third Doctor's period, were introduced partly as an effort to reduce production costs when the series moved into colour by Peter Bryant and Derrick Sherwin, the show's previous producer and script editor, as well as to base the series more on The Quatermass Experiment (1953).

Edward Burnham portrays Professor Kettlewell, the wild-haired, bespectacled boffin who creates the titular K1 robot.[13] Along with Courtney and Levene, Burnham had also appeared in The Invasion, where he played another scientist, Professor Watkins. The part of the K1 robot is played by Michael Kilgarriff[13] who had played another robotic part in The Tomb of the Cybermen (1967), the Cyberman Controller. Patricia Maynard is cast in the part of Miss Hilda Winters, the director of the National Institute for Advanced Scientific Research.[13] Miss Winters' assistant, Arnold Jellicoe, is played by Alec Linstead.[13] Linstead had played the part of Sergeant Osgood—a member of the technical staff at UNIT—in The Dæmons (1971).

Filming

[edit]This was the first serial to be produced for the season.[14] This was also the first Doctor Who serial to have its location material shot entirely on videotape using outside broadcasting facilities, as opposed to the more usual BBC television drama practice of the time of shooting studio interiors on videotape and location exteriors on 16 mm film. This was due to the large number of video effects involving the eponymous robot required in exterior scenes (shot at the then BBC Engineering Training Department at Wood Norton, Worcestershire[13][15]), which were easier and more convincing to marry to videotape than to film. The team had learned that lesson during the previous season's Invasion of the Dinosaurs. The Wood Norton facility was chosen for location shooting because it had an underground bunker, which director Christopher Barry felt would be suitable for the entrance to the underground complex in the story; however, they were refused permission to shoot in that area.[15]

Broadcast and reception

[edit]| Episode | Title | Run time | Original air date | UK viewers (millions) [16] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | "Part One" | 24:11 | 28 December 1974 | 10.8 |

| 2 | "Part Two" | 25:00 | 4 January 1975 | 10.7 |

| 3 | "Part Three" | 24:29 | 11 January 1975 | 10.1 |

| 4 | "Part Four" | 24:29 | 18 January 1975 | 9.0 |

Robot was the first serial of the twelfth season of Doctor Who. Part one of Robot was first broadcast on BBC One on Saturday, 28 December 1974[13][14] and had a viewership of 10.8 million, which was higher than the first serial for season eleven. The next three parts were broadcast over the next successive Saturdays, each having an audience of over 10 million with the exception of the part four on Saturday, 18 January 1975 which only had viewership of 9 million.[13]

Reception

[edit]

Viewer reaction was mixed as defined in an Audience Research Report conducted by the BBC. About 30% felt the show was "definitely enjoyable" with a lower percentage being "distinctly unimpressed". A number of viewers thought the new Doctor would "take some getting used to", but most younger viewers gave positive comments about the serial.[3][7] As with all of the Doctors, Baker received some criticism by the audience, who felt he was a "loony" and presented as "stupid".[17]

Writing for Doctor Who Bulletin in 1988, Jonathan Way felt the serial was fun,[18] and for the same publication, Robert Cope praised Baker's performance as the new Doctor, also noting that the relationship between Baker's Doctor and Sladen's Sarah worked well.[19] David J. Howe and Stephen James Walker, writing in The Television Companion, admired the performances of Nicholas Courtney and Elisabeth Sladen and felt Marter's debut as Harry Sullivan was promising. They also commended the K1 robot costume, but criticised the use of CSO (colour-separation overlay) effects for a number of shots involving the K1 robot, as did Robert Cope.[3][7][19] In Doctor Who Episode by Episode, Ray Dexter described Baker's "over-the-top" performance as "compelling" but the plot as "a little lazy and derivative, with some terrible science." He considered the dialogue "some of the best we've seen" but added that "the story falls into the typical Dicks trap of just having baddies being bad because they're bad, and a logical robot behaving utterly illogically". He also thought the location work on video "cheapens the look of the show" and criticised the effects as "not good enough, not even for this era".[20]

Mark Braxton of Radio Times awarded the serial three stars out of five, praising the introduction of Baker and Marter, as well as the K1 concept. However, he felt that the villains were stereotypical and wrote that Robot "boasts perhaps the show's worst visual effect ever".[13] IGN reviewer Arnold Blumburg gave the story a rating of 7 out of 10, attributing its success to Baker. He too criticised the effects, feeling that it made the story "[fail] when trying to present an epic conclusion".[21] DVD Talk's Nick Lyons wrote that it "may not be the most original episode, but it is one of the stronger episodes of the Baker years simply because it never drags and is a breezy action-adventure. It doesn't hurt that the robot itself is a nifty villain". He gave the serial three and a half out of five stars.[22] In 2010, SFX named the scene where the Doctor tries on many different costumes as one of the silliest moments in the show's history.[23]

Reviewing the serial in 2007, literary critic John Kenneth Muir noted several influences on the writing of Robot. Kettlewell's K1 robot is programmed so that it cannot harm humans; Muir traces the inspiration for this directly from the Three Laws of Robotics devised by Isaac Asimov in his 1950 story collection, I, Robot. He also considers the relationship of Sarah Jane Smith with the K1 robot, its transformation into gigantic antagonist (holding a captive damsel in distress, Sarah, in its claw) and its tragic destruction by military force as an analogue of the 1933 film, King Kong.[4]

Commercial releases

[edit]Robot has had a number of commercial releases on video, in print, audio and other merchandise.

In print

[edit] | |

| Author | Terrance Dicks |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Peter Brookes |

| Series | Doctor Who book: Target novelisations |

Release number | 28 |

| Subject | Featuring: Sarah Jane Smith, the Brigadier, Harry Sullivan |

| Publisher | Target Books |

Publication date | 13 March 1975 |

| Pages | 124 |

| ISBN | 0-426-10858-2 |

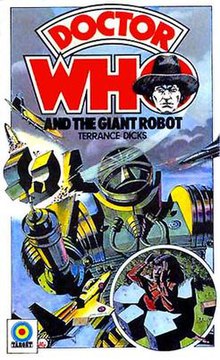

A novelisation of this serial, written by Terrance Dicks, was published by Target Books in 1975, titled Doctor Who and the Giant Robot.[24] A second edition was released in 1978 by W. H. Allen Ltd with new cover art; a third edition, retitled Doctor Who – Robot and using the VHS release artwork, was released in 1992.[24]

It was also one of two Doctor Who serials to have a second novelisation written, aimed at younger readers using simpler language (the other being Junior Doctor Who and the Brain of Morbius). Also written by Dicks, this edition was titled Junior Doctor Who and the Giant Robot.[25]

Audio book

[edit]An unabridged reading of the novelisation by actor Tom Baker was released on compact disc on 5 November 2007 by BBC Audiobooks.[26] The audio book was released as Doctor Who: The Giant Robot on 4 CDs for an American audience in 2008 by Chivers Children's Audio Books.[12][27] The audio book was released a third time as a pre-loaded Playaway digital audio book in 2009 by BBC Audiobooks.[28]

Home media

[edit]Robot first entered the home video market as a VHS release in February 1992.[24] The North American VHS release occurred in 1994 when CBS/Fox Video released the serial.[29]

BBC Video first released Robot on DVD in the United Kingdom on 4 June 2007.[30][31] It was released later in the United States on 14 August 2007.[22] The DVD release received generally positive reviews and was praised for the extras, including a documentary titled Are Friends Electric? detailing the production and casting of the show.[21][22][30] Robot was released as part of issue 49 of Doctor Who DVD Files, published 17 November 2010.

Other merchandise

[edit]Denys Fisher Toys released an 8" posable action figure of Robot K1 named "Doctor Who Giant Robot" in 1976.[32]

Eaglemoss Collections released a special issue magazine that included a hand painted figurine of Robot K1 on 2 September 2014. It was presented as the fourth special in the Doctor Who Figurine Collection.

Doctor Who Battles in Time released a rare card number 787 of Robot K1 in the Ultimate Monsters which was part of the other card category collections of Exterminator, Annihilator, Invader and Devastator.

References

[edit]- ^ Leach, Jim (1 April 2009). "Doctor Who": TV Milestones Series (illustrated ed.). Detroit, Michigan, US: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 9780814333082. OCLC 768120206. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ^ Richmond, Caroline (13 October 2006). "Allister Bowtell". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ a b c d BBC staff (2007). "BBC – Doctor Who Classic Episode Guide – Robot – Details". Doctor Who The Classic Series. BBC. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ a b Muir, John Kenneth (1999). "Season 12". A critical history of Doctor Who on television (illustrated ed.). Jefferson, North Carolina, US: McFarland & Company. pp. 222–223. ISBN 9780786404421. OCLC 40926632. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ^ "BBC – Doctor Who Classic Episode Guide – Robot – Details". BBC.

- ^ Cornell, Paul; Day, Martin; Topping, Keith (1 October 2004). The Discontinuity Guide: The Unofficial Doctor Who Companion (2nd ed.). Austin, Texas, US: MonkeyBrain Books. ISBN 9781932265095. OCLC 56773449. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ a b c Howe, David J.; Walker, Stephen James (30 October 2004). The Television Companion: The Unofficial and Unauthorised Guide to Doctor Who. Tolworth, Surrey, England, UK: Telos Publishing. ISBN 9781903889527. OCLC 59332938. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ^ Sladen, Elisabeth (2012). Doctor Who Stories: Elizabeth Sladen Part 1 (DVD). Vol. Doctor Who: Invasion of the Dinosaurs. London, England, UK: BBC Video. ISBN 9780780684416. OCLC 750279801.

- ^ a b

Westthorp, Alex (24 April 2008). "Who could've been Who? An alternate history of Doctor Who". Den of Geek. London, England, UK: Dennis Publishing. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

Eventually a suggestion by the wife of BBC drama head Bill Slater was followed up and the production team found the wild-eyed and naturally eccentric Tom Baker mixing cement on a building site.

- ^ a b c

Westthorp, Alex (1 April 2010). "Top 10 Doctor Who producers: Part Two". Den of Geek. London, England, UK: Dennis Publishing. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

Letts found casting a new Doctor more difficult, however, until a tip-off from his boss Bill Slater. An unemployed actor, then working on a building site, called Tom Baker had written to Slater asking for work. In, arguably, one of the best decisions ever made on Doctor Who, Letts cast Tom Baker as the fourth Doctor.

- ^

Rawson-Jones, Ben (14 October 2009). "A tribute to 'Doctor Who' legend Barry Letts". Digital Spy. New York City, New York, US. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

Having seen unknown hod-carrier Baker in The Golden Voyage of Sinbad, Letts took the goggle-eyed aspiring actor away from the building site and into the Tardis in 1974.

- ^ a b AudioFile staff (July 2009). Whitten, Robin F. (ed.). "AudioFile audiobook review: DOCTOR WHO By Terrance Dicks, Read by Tom Baker". AudioFile. Portland, Maine, US: AudioFile Publications. ISSN 1063-0244. OCLC 25844569. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Braxton, Mark (7 May 2010). Preston, Ben (ed.). "Doctor Who: Robot – Radio Times". Radio Times. London, England, UK: Immediate Media Company. ISSN 0033-8060. OCLC 240905405. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ a b Lofficier, Jean-Marc; Jean-Marc; Randy, Lofficier (1 May 2003). The Doctor Who Programme Guide: Fourth Edition (4th ed.). Bloomington, Indiana, US: iUniverse. p. 118. ISBN 9780595276189. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- ^ a b Howe, David J.; Stammers, Mark; Walker, Stephen James (1 November 1992). The Fourth Doctor Handbook: The Tom Baker Years 1974–1981. London, England, UK: Doctor Who Books. p. 214. ISBN 9780426203698. OCLC 31709926.

- ^ "Ratings Guide". Doctor Who News. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- ^ "Doctor Who regeneration was 'modelled on LSD trips'". BBC News. 12 April 2010. Retrieved 19 January 2013.

- ^ Way, Jonathan (December 1988). Leigh, Gary (ed.). "A Voyage Through 25 Years of Doctor Who". Doctor Who Bulletin. No. #61, 25th Anniversary Special. Brighton, England, UK: Titan Magazines. ISSN 1351-2471. OCLC 500077966.

- ^ a b

Cope, Robert (December 1991). Leigh, Gary (ed.). "(unknown)". Doctor Who Bulletin. No. 96. Brighton, England, UK: Titan Magazines. ISSN 1351-2471. OCLC 500077966.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite uses generic title (help) - ^ Dexter, Ray (2012). Doctor Who Episode By Episode: Volume 4 Tom Baker. Lulu.com. ISBN 9781291174076.

- ^ a b Blumberg, Arnold (13 August 2007). "Doctor Who: Robot DVD Review – IGN". IGN Entertainment. San Francisco, California, US: News Corporation. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ a b c Lyons, Nick (30 September 2007). "Doctor Who – Robot : DVD Talk Review of the DVD Video". DVD Talk. El Segundo, California, US: Internet Brands. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ O'Brian, Steve (November 2010). "Doctor Who's 25 Silliest Moments". SFX. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- ^ a b c Lofficier, Jean-Marc and Randy (1 May 2003). "Fourth Doctor". The Doctor Who Programme Guide. iUniverse. p. 119. ISBN 0595276180.

- ^ "Publication: Doctor Who and the Giant Robot: A Junior Doctor Who Book". isfdb.org.

- ^ Doctor Who and the Giant Robot (CD). Bath, Somerset, England, UK: BBC Audiobooks. 2007. ISBN 9781405666671. OCLC 212781264.

- ^ Doctor Who: The Giant Robot (CD). North Kingstown, Rhode Island, US: Chivers Children's Audio Books. 2008. ISBN 9781405657914. OCLC 271893995.

- ^ Doctor Who and the Giant Robot (Digital audio). Bath, Somerset, England, UK: BBC Audiobooks. 2009. ISBN 9781408415313. OCLC 752431922.

- ^ Doctor Who / Robot (VHS). New York City, New York, US: CBS/Fox Video. 1994. ISBN 9780793981038. OCLC 33954409.

- ^ a b Wilkins, Jonathan (15 May 2007). "Doctor Who: Robot Reviews – Total Sci-Fi". Dreamwatch. Brighton, England, UK: Titan Magazines. ISSN 1351-2471. OCLC 500077966. Archived from the original on 7 June 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2013.

- ^ Doctor Who / Robot (DVD). London, England, UK: BBC Video. 2007. ISBN 9781419858604. OCLC 156824505.

- ^ "Doctor Who Giant Robot". 19 February 1976.

Bibliography

[edit]- Howe, David J.; Stammers, Mark; Walker, Stephen James (1 November 1995). Doctor Who: The Seventies (illustrated ed.). London, England, UK: Doctor Who Books. ISBN 9780863698712. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- Pixley, Andrew (3 May 2000). Spilsbury, Tom (ed.). "Archive: Robot". Doctor Who Magazine. No. 290. Modena, Italy: Panini Comics. ISSN 0957-9818.

- Pixley, Andrew (1 September 2004). Spilsbury, Tom (ed.). "You Ain't Seen Nothing Yet". Doctor Who Magazine. No. Special Edition #8. Modena, Italy: Panini Comics. ISSN 0957-9818.

- Richards, Justin; Anghelides, Peter (January 1988). "Production". In-Vision. No. #1. Warwickshire, England, UK: CyberMark Services. ISSN 0953-3303.

External links

[edit]- Robot at BBC Online

Target novelisation

[edit]- Doctor Who and the Giant Robot title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database