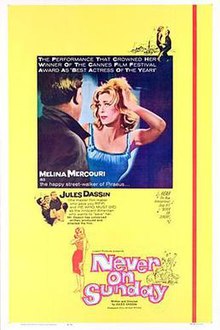

Never on Sunday

| Never on Sunday | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Jules Dassin |

| Written by | Jules Dassin |

| Starring | Melina Mercouri Jules Dassin Giorgos Fountas |

| Cinematography | Jacques Natteau |

| Edited by | Roger Dwyre |

| Music by | Manos Hatzidakis |

Production company | Melina Film |

| Distributed by | Lopert Pictures Corporation (United States) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 91 minutes |

| Country | Greece |

| Languages | Greek English Russian |

| Budget | $150,000[1][2] |

| Box office | $4 million (rentals)[3] |

Never on Sunday (Greek: Ποτέ την Κυριακή, Poté tin Kyriakí) is a 1960 Greek romantic comedy film starring, written by and directed by Jules Dassin.

The film tells the story of Ilya, a contented Greek prostitute (Melina Mercouri), and Homer (Dassin), an earnest American classicist. Homer attempts to steer her toward morality while Ilya attempts to make Homer more relaxed. The original screenplay examines the impact of intellectual imperialism upon indigenous Joie de vivre. It constitutes a variation of the Pygmalion plus "hooker with a heart of gold" story.[4]

The film's bouzouki theme became a hit and the film won the Academy Award for Best Original Song (Manos Hadjidakis for "Never on Sunday"). It was nominated for Academy Awards for Best Actress in a Leading Role (Mercouri), Best Costume Design, Black-and-White, Best Director and Best Writing, Story and Screenplay as Written Directly for the Screen (both Dassin). Mercouri won the award for Best Actress at the 1960 Cannes Film Festival.[5]

Synopsis

[edit]Ilya, a self-employed, free-spirited prostitute who lives in the port of Piraeus in Greece, meets Homer Thrace, an American tourist and classical scholar and passionate Philhellene. Homer feels that Ilya's promiscuity typifies the epicurean degradation of Greek classical culture and attempts to steer her onto the path of morality while Ilya attempts to relax him and avoid his getting into unnecessary arguments and fights.

Plot

[edit]Self-employed prostitute and free spirit Ilya, in the port city of Piraeus, Greece, has a dedicated following of preferred “clients” whom she entertains at weekly receptions on Sundays, a day she takes off from “business.” At the shipyard, when Ilya impulsively strips off her clothes to dive in for a dip in the ocean in her underwear, she challenges the “slaves” to join her, and many workers enthusiastically dive in. On his first day, Tonio, a half-Italian worker, becomes infatuated with the beautiful Ilya. He learns that popular Ilya “sets no prices and only goes with a client if she likes him.” When Tonio asks Ilya if he has a chance with her that evening, Ilya teases him, saying she will be busy with the baker, the fruit man, and the butcher. Tonio becomes determined to win over Ilya exclusively for himself.

Homer Thrace, an American scholar of classical Hellenic culture, believes that Ilya personifies how Greek culture decayed due to living by Stoic and Epicurean philosophies. According to Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, as Homer believes, the great happiness is the joy of understanding. By contrast, Ilya sees life through her own idiosyncratic perspective, filtering out the negative. When Homer accompanies Ilya to see a performance of the classical drama Medea, Ilya sees Medea as a caring mother and wife who tricks her husband to win him back from a rival. Ilya refuses to accept that Medea is a ruthless wife who kills her own children to take revenge on her husband. Homer finds Ilya’s relentlessly upbeat perspective incomprehensible. Despite Ilya’s clients urging Homer to leave Ilya as she is, Homer sees himself as Pygmalion, determined to mold Ilya into Galatea, reforming the prostitute to a happy moral life.

“Noface”, whose naked face behind large sunglasses no one ever sees, owns apartment houses where prostitutes pay him high “rents” to work. The prostitutes threaten to strike unless Noface lowers the rents. Noface considers the independent Ilya a bad example. Despo, leader of the striking prostitutes, appeals to Ilya, who has influence, to encourage all the prostitutes to stop working to join the strike. Noface offers to finance Homer’s experiment to reform Ilya, suggesting Homer “buy” Ilya’s time. Since they both have the same goal of putting Ilya out of business, though for different reasons, Homer accepts the money from Noface. To this end, Homer proposes to Ilya to conduct a two-week experiment, offering to pay her for her exclusive time to give her lessons in classical subjects and culture.

Ilya attempts to please Homer by studying the books and listening to the records he gives her but is bored. Meanwhile Ilya’s clients, including Tonio, are disgruntled when denied her services. When Ilya hears the whistle of a ship arriving, she is unhappy that she must study rather than party with the sailors.

At the end of the two-week period, when Noface pays Homer for his expenses, Despo sees the transaction and immediately informs Ilya. Ilya reacts by leading the other prostitutes in their strike against Noface, refusing to work and throwing their headboards and mattresses out the windows. The prostitutes are arrested, but Noface’s lawyer pays their fines and negotiates with Ilya to reduce the rents by 50%. Tonio and his friends arrive to get Ilya, taking her to their local bar, where typically, Homer is in trouble because the know-it-all has told the guitar player that he is not a real musician if he cannot read music.

Homer tells Ilya that she’s beautiful but dumb, and he laments that he wanted to save her. Tonio replies, "Ilya is not a symbol, she’s a woman." Homer tells Ilya that indeed he wanted to make love to her but restrained himself. Tonio declares its “too late” because he is going to take Ilya back to Italy for a new life, sweeping Ilya off her feet and carrying her away. The bar owner tells Homer, “If anyone will save Ilya, it will be Tonio…because with love, it’s possible.”

Homer boards a ship back to the US, throwing away his notes.

"And they all go to the seashore!"

Cast

[edit]- Melina Mercouri as Ilya

- Jules Dassin as Homer Thrace

- Giorgos Fountas as Tonio

- Titos Vandis as Jorgo

- Mitsos Ligizos as The Captain (as Mitsos Lygizos)

- Despo Diamantidou as Despo

- Dimos Starenios as Poubelle

- Dimitris Papamichael as Sailor (as Dimitri Papamichael)

- Alexis Solomos as Noface

- Thanassis Veggos

- Phaedon Georgitsis as Sailor

- Nikos Fermas as Waiter

Reception

[edit]When the film was first released in Italy in 1960, the Committee for the Theatrical Review of the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities rated it as VM16, not suitable for children under 16. The committee also demanded dialogue modifications and the excision of explicit scenes.[6]

Bosley Crowther of The New York Times praised the movie as a "droll and robust spoof" and commended Mercouri's and Dassin's "superb" performances:

It is the bouncing and beaming expansiveness with which Miss Mercouri endows this woman and the patience with which Mr. Dassin tries to urge her to simmer down, to assume a little moral decorum and abandon some of her non-intellectual and professional whims, that make for tremendous good humor.... **** While one might take some minor exception to the occasional illogic of the script, it's no use, since illogic is the human disposition most frankly acknowledged and happily applauded in this film.[7]

Home media

[edit]MGM released Never on Sunday on VHS in 2000 as part of its Vintage Classics lineup.

Stage adaptation

[edit]Dassin and Mercouri adapted the film for Broadway as a musical, titled Illya Darling, starring Mercouri again in the title role.[8] She was nominated for the Tony Award for Best Actress in a Musical for her performance.

References

[edit]- ^ Tino Balio, United Artists: The Company That Changed the Film Industry, University of Wisconsin Press, 1987 p. 127

- ^ "On $151,000 Negative Cost, Forsee 'Never On Sunday' Rentals of $8 mill". Variety. 1 November 1961. p. 1.

- ^ "All-Time Top Grossers", Variety, 8 January 1964 p 69

- ^ Christopher Bonano, Gods, Heroes, And Philosophers, p. 53

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Never on Sunday". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 2024-02-29.

- ^ Italia Taglia Database of the documents produced by the Committee for the Theatrical Review of The Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities, from 1944 to 2000.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (19 October 1960). "An American in Piraeus: Greek Film, 'Never on Sunday,' in Debut". Retrieved 28 December 2024 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ Tams Witmark Illya Darling accessed 06/24/2023

External links

[edit]- 1960 films

- 1960 romantic comedy films

- 1960s sex comedy films

- 1960s English-language films

- English-language Greek films

- 1960s Greek-language films

- Greek black-and-white films

- Films about prostitution in Greece

- Films set in Greece

- Films shot in Greece

- Films that won the Best Original Song Academy Award

- Films directed by Jules Dassin

- Greek multilingual films

- Piraeus

- Films scored by Manos Hatzidakis

- Greek romantic comedy films

- 1960s multilingual films

- Censored films

- English-language sex comedy films

- English-language romantic comedy films