Portugal

Portuguese Republic República Portuguesa (Portuguese) | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: A Portuguesa "The Portuguese" | |

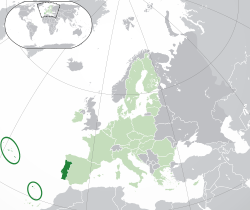

Location of Portugal (dark green) – in Europe (green & dark grey) | |

| Capital and largest city | Lisbon 38°46′N 9°9′W / 38.767°N 9.150°W |

| Official languages | Portuguese |

| Recognised regional languages | Mirandese[a] |

| Nationality (2023)[3] |

|

| Religion (2021)[4] |

|

| Demonym(s) | Portuguese |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential republic[5][b] |

| Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa | |

| Luís Montenegro | |

• Speaker | José Pedro Aguiar-Branco |

| Legislature | Assembly of the Republic |

| Establishment | |

• County | 868 |

| 24 June 1128 | |

• Kingdom | 25 July 1139 |

| 5 October 1143 | |

| 23 May 1179 | |

| 23 September 1822 | |

• Republic | 5 October 1910 |

| 25 April 1974 | |

| 25 April 1976[c] | |

| Area | |

• Total | 92,230 km2 (35,610 sq mi)[7][8] (109th) |

• Water (%) | 1.2 (2015)[6] |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | |

• 2021 census | |

• Density | 115.4/km2 (298.9/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2023) | medium inequality |

| HDI (2022) | very high (42nd) |

| Currency | Euro[d] (€) (EUR) |

| Time zone | UTC (WET) UTC−1 (Atlantic/Azores) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (WEST) UTC (Atlantic/Azores) |

| Note: Continental Portugal and Madeira use WET/WEST; the Azores are 1 hour behind. | |

| Drives on | Right |

| Calling code | +351 |

| ISO 3166 code | PT |

| Internet TLD | .pt |

Portugal,[e] officially the Portuguese Republic,[f] is a country in the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it shares the longest uninterrupted border in the European Union; to the south and the west is the North Atlantic Ocean; and to the west and southwest lie the Macaronesian archipelagos of the Azores and Madeira, which are two autonomous regions of Portugal. Lisbon is the capital and largest city, followed by Porto, which is the only other metropolitan area.

The western part of the Iberian Peninsula has been continuously inhabited since prehistoric times, with the earliest signs of settlement dating to 5500 BC.[14] Celtic and Iberian peoples arrived in the first millennium BC. The region came under Roman control in the second century BC, followed by a succession of Germanic peoples and the Alans from the fifth to eighth centuries AD. Muslims conquered the entirety of Portugal's current mainland in the eighth century, but they were gradually expelled by the Christian Reconquista over the next several centuries. Modern Portugal began taking shape during this period, initially as a county of the Christian Kingdom of León in 868, officially declared a sovereign Kingdom with the Treaty of Zamora in 1143.[15]

During the Age of Discovery, the Kingdom of Portugal settled Madeira and the Azores, and established itself as a major economic and political power, largely through its maritime empire, which extended mostly along the South Atlantic and Indian Ocean coasts.[16] Portuguese explorers and merchants were instrumental in establishing trading posts and colonies that enabled control over spices and slave trades.[17] While Portugal expanded its influence globally, its political and military power faced internal and external challenges towards the end of the 16th century. The dynastic crisis marked the beginning of the country's political decline that led to the Iberian Union (1580-1640), a period in which Portugal was united under Spanish rule.[18] While maintaining a degree of self-governance, the union strained Portugal’s autonomy and drew it into conflicts with European powers which targeted Portuguese territories and trade routes.[19] Portugal's prior opulence was further diminished by a series of events, such as the Portuguese Restoration War and the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, which destroyed the city and damaged the empire's economy.[20]

The Napoleonic Wars motivated the Portuguese royal family to relocate to Brazil in 1807. This event reshaped the relationship between Portugal and Brazil, culminating in Brazilian independence in 1822,[21] which indirectly led to a civil war between liberals and absolutists from 1828 to 1834.[22] The monarchy was overthrown in the 5 October 1910 revolution, which led to the establishment of the Portuguese First Republic. A phase of unrest ultimately led to the rise of authoritarian regimes of the Ditadura Nacional and the Estado Novo.[23] Democracy was finally restored following the Carnation Revolution of 1974, and brought an end to the Portuguese Colonial War, allowing the last of Portugal’s African territories to achieve independence.[24]

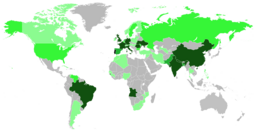

Portugal's imperial history has left a cultural legacy, with around 300 million Portuguese speakers around the world. Today, it is a developed country with an advanced economy relying chiefly upon services, industry, and tourism. Portugal, a member of the United Nations, the European Union, the Schengen Area, and the Council of Europe, was one of the founding members of NATO, the eurozone, the OECD, and the Community of Portuguese Language Countries.

Etymology

The word Portugal derives from the combined Roman-Celtic place name Portus Cale[25][26] (present-day's conurbation of Porto and Vila Nova de Gaia). Porto stems from the Latin for port, portus; Cale's meaning and origin is unclear. The mainstream explanation is an ethnonym derived from the Callaeci, also known as the Gallaeci peoples, who occupied the north-west of the Iberian Peninsula.[27] One theory proposes Cale is a derivation of the Celtic word for 'port'.[28] Another is that Cala was a Celtic goddess. Some French scholars believe it may have come from Portus Gallus,[29] the port of the Gauls.

Around 200 BC, the Romans took Iberia from the Carthaginians during the Second Punic War. In the process they conquered Cale, renaming it Portus Cale ('Port of Cale') and incorporating it into the province of Gallaecia. During the Middle Ages, the region around Portus Cale became known by the Suebi and Visigoths as Portucale. The name Portucale changed into Portugale during the 7th and 8th centuries, and by the 9th century, it was used to refer to the region between the rivers Douro and Minho. By the 11th and 12th centuries, Portugale, Portugallia, Portvgallo or Portvgalliae was already referred to as Portugal.

History

Prehistory

The region has been inhabited by humans since circa 400,000 years ago, when Homo heidelbergensis entered the area. The oldest human fossil found in Portugal is the 400,000-year-old Aroeira 3 H. Heidelbergensis skull discovered in the Cave of Aroeira in 2014.[30] Later Neanderthals roamed the northern Iberian peninsula and a tooth has been found at Nova da Columbeira cave in Estremadura.[31] Homo sapiens sapiens arrived in Portugal around 35,000 years ago and spread rapidly.[32] Pre-Celtic tribes inhabited Portugal. The Cynetes developed a written language, leaving stelae, which are mainly found in the south.

Early in the first millennium BC, several waves of Celts invaded Portugal from Central Europe and intermarried with the local populations to form several different ethnic groups. The Celtic presence is patent in archaeological and linguistic evidence. They dominated most of northern and central Portugal, while the south maintained its older character (believed non-Indo-European, likely related to Basque) until the Roman conquest.[33] In southern Portugal, some small, semi-permanent commercial coastal settlements were also founded by Phoenicians and Carthaginians.

Roman Portugal

Romans first invaded the Iberian Peninsula in 219 BC. The Carthaginians, Rome's opponent in the Punic Wars, were expelled from their coastal colonies. During Julius Caesar's rule, almost the entire peninsula was annexed to Rome. The conquest took two hundred years and many died, including those sentenced to work in slave mines or sold as slaves to other parts of the empire. Roman occupation suffered a setback in 155 BC, when a rebellion began in the north. The Lusitanians and other native tribes, under the leadership of Viriathus,[34][35] wrested control of all of western Iberia. Rome sent legions to quell the rebellion but were unsuccessful. Roman leaders bribed Viriathus's allies to kill him in 139 BC; he was replaced by Tautalus.

In 27 BC, Lusitania gained the status of Roman province. Later, a northern province was separated from the province of Tarraconensis, under Emperor Diocletian's reforms, known as Gallaecia.[36] There are still ruins of castros (hill forts) and remains of the Castro culture, like Conímbriga, Mirobriga and Briteiros.

Germanic kingdoms

In 409, with the decline of the Roman Empire, the Iberian Peninsula was occupied by Germanic tribes.[37] In 411, with a federation contract with Emperor Honorius, many of these people settled in Hispania. An important group was made up of the Suebi and Vandals in Gallaecia, who founded a Suebi Kingdom with its capital in Braga. They came to dominate Aeminium (Coimbra) as well, and there were Visigoths to the south.[38] The Suebi and the Visigoths were the Germanic tribes who had the most lasting presence in the territories corresponding to modern Portugal. As elsewhere in Western Europe, there was a sharp decline in urban life during the Dark Ages.[39]

Roman institutions disappeared in the wake of the Germanic invasions with the exception of ecclesiastical organisations, which were fostered by the Suebi in the fifth century and adopted by the Visigoths afterwards. Although the Suebi and Visigoths were initially followers of Arianism and Priscillianism, they adopted Catholicism from the local inhabitants. St. Martin of Braga was a particularly influential evangelist.[38]

In 429, the Visigoths moved south to expel the Alans and Vandals and founded a kingdom with its capital in Toledo. From 470, conflict between the Suebi and Visigoths increased. In 585, the Visigothic King Liuvigild conquered Braga and annexed Gallaecia; the Iberian Peninsula was unified under a Visigothic Kingdom.[38] A new class emerged, unknown in Roman times: a nobility, which played a key social and political role during the Middle Ages. It was under the Visigoths that the Church began to play an important part within the state. As the Visigoths did not learn Latin from the local people, they had to rely on bishops to continue the Roman system of governance. The laws were made by councils of bishops, and the clergy emerged as a high-ranking class.

Islamic period

Today's continental Portugal, along with most of modern Spain, was invaded from the South and became part of al-Andalus between 726 and 1249, following the Umayyad Caliphate conquest of the Iberian Peninsula. This rule lasted decades in the North, up to five centuries in the South.[40]

After defeating the Visigoths in a few months, the Umayyad Caliphate started expanding rapidly in the peninsula. Beginning in 726, the land that is now Portugal became part of the vast Umayyad Caliphate's empire of Damascus, until its collapse in 750. That year the west of the empire gained its independence under Abd-ar-Rahman I with the establishment of the Emirate of Córdoba. The Emirate became the Caliphate of Córdoba in 929, until its dissolution in 1031, into 23 small kingdoms, called Taifa kingdoms.[40]

The governors of the taifas proclaimed themselves Emir of their provinces and established diplomatic relations with the Christian kingdoms of the north. Most of present-day Portugal fell into the hands of the Taifa of Badajoz of the Aftasid Dynasty, and in 1022 the Taifa of Seville of the Abbadids poets. The Taifa period ended with the conquest of the Almoravids in 1086, then by the Almohads in 1147.[41] Al-Andaluz was divided into districts called Kura. Gharb Al-Andalus at its largest consisted of ten kuras,[42] each with a distinct capital and governor. The main cities were in the southern half of the country: Beja, Silves, Alcácer do Sal, Santarém and Lisbon. The Muslim population consisted mainly of native Iberian converts to Islam and Berbers.[43] The Arabs (mainly noblemen from Syria) although a minority, constituted the elite. The Berbers who joined them, were nomads from the Rif Mountains of North Africa.[40]

Invasions from the North also occurred in this period, with Viking incursions raiding the coast between the 9th and 11th centuries, including Lisbon.[44][45] This resulted in the establishment of small Norse settlements in the coastline between Douro and Minho.[46]

Reconquista

The Reconquista was a period when Christians reconquered the Iberian Peninsula from Moorish domination. An Asturian Visigothic noble named Pelagius of Asturias was elected leader in 718[47] by many of the ousted Visigoth nobles. Pelagius called for the remnants of the Christian Visigothic armies to rebel against the Moors and regroup in the unconquered northern Asturian highlands, known today as the Cantabrian Mountains, in north-west Spain.[48] After defeating the Moors in the Battle of Covadonga in 722, Pelagius was proclaimed king, thus founding the Christian Kingdom of Asturias and starting the war of Christian reconquest.[48]

At the end of the 9th century, the region of Portugal between the rivers Minho and Douro, was reconquered from the Moors by nobleman and knight Vímara Peres on the orders of King Alfonso III of Asturias.[49] Finding many towns deserted, he decided to repopulate and rebuild them.[50]

Vímara Peres elevated the region to the status of County, naming it the County of Portugal after its major port city – Portus Cale or modern Porto. One of the first cities he founded is Vimaranes, known today as Guimarães – "birthplace of the Portuguese nation" or the "cradle city".[50]

After annexing the County of Portugal into one of the counties that made up the Kingdom of Asturias, King Alfonso III of Asturias knighted Vímara Peres, in 868, as the First Count of Portus Cale (Portugal). The region became known as Portucale, Portugale, and simultaneously Portugália.[50] With the forced abdication of Alfonso III in 910, the Kingdom of Asturias split into three separate kingdoms; they were reunited in 924 under the crown of León.

In 1093 Alfonso VI of León bestowed the county to Henry of Burgundy and married him to his daughter, Teresa of León. Henry thus became Henry, Count of Portugal and based his newly formed county from Bracara Augusta (modern Braga).

Independence

At the Battle of São Mamede, in the outskirts of Guimarães, in 1128, Afonso Henriques, Count of Portugal, defeated his mother Countess Teresa and her lover Fernão Peres de Trava, establishing himself as sole leader of the county. Afonso continued his father Henry of Burgundy's Reconquista wars. His campaigns were successful and in 1139, he obtained a victory in the Battle of Ourique, so was proclaimed King of Portugal by his soldiers. This is traditionally taken as the occasion when the County of Portugal became the independent Kingdom of Portugal and, in 1129, the capital city was transferred from Guimarães to Coimbra. Afonso was recognized as the first king of Portugal in 1143 by King Alfonso VII of León, and in 1179 by Pope Alexander III as Afonso I of Portugal. Afonso Henriques and his successors, aided by military monastic orders, continued pushing southwards against the Moors. In 1249, the Reconquista ended with the capture of the Algarve and expulsion of the last Moorish settlements. With minor readjustments, Portugal's territorial borders have remained the same, making it one of the oldest established nations in Europe.

After a conflict with the kingdom of Castile, Denis of Portugal signed the Treaty of Alcañices in 1297 with Ferdinand IV of Castile. This treaty established the border between the kingdoms of Portugal and Leon. The reigns of Denis, Afonso IV, and Peter I mostly saw peace with the other kingdoms of Iberia.

In 1348-49 Portugal, as with the rest of Europe, was devastated by the Black Death.[51] In 1373, Portugal made an alliance with England, the oldest standing alliance in the world.

Age of Discoveries

In 1383 John I of Castile, Beatrice of Portugal, and Ferdinand I of Portugal claimed the throne of Portugal. John of Aviz, later John I of Portugal, defeated the Castilians in the Battle of Aljubarrota, and the House of Aviz became the ruling house. The new ruling dynasty led Portugal to the limelight of European politics and culture. They created and sponsored literature, such as a history of Portugal, by Fernão Lopes.[52][53][54]

Portugal spearheaded European exploration of the world and the Age of Discovery under the sponsorship of Prince Henry the Navigator. Portugal explored the Atlantic, encountering the Azores, Madeira, and Portuguese Cape Verde, which led to the first colonisation movements. The Portuguese explored the Indian Ocean, established trade routes in most of southern Asia, and sent the first direct European maritime trade and diplomatic missions to China (Jorge Álvares) and Japan (Nanban trade). In 1415, Portugal acquired its first colonies by conquering Ceuta, in North Africa. Throughout the 15th century, Portuguese explorers sailed the coast of Africa, establishing trading posts for commodities, ranging from gold to slavery. Portugal sailed the Portuguese India Armadas to Goa via the Cape of Good Hope.

The Treaty of Tordesillas of 1494 was intended to resolve a dispute created following the return of Christopher Columbus and divided the newly located lands outside Europe between Portugal and Spain along a line west of the Cape Verde islands, off the west coast of Africa. In 1498 Vasco da Gama became the first European to reach India by sea, bringing economic prosperity to Portugal and helping to start the Portuguese Renaissance. In 1500, the Portuguese explorer Gaspar Corte-Real reached what is now Canada and founded the town of Portugal Cove-St. Philip's, one of many Portuguese colonies of the Americas.[55][56][57]

In 1500, Pedro Álvares Cabral landed on Brazil and claimed it for Portugal.[58] Ten years later, Afonso de Albuquerque conquered Goa in India, Muscat and Ormuz in the Persian Strait, and Malacca, now in Malaysia. Thus, the Portuguese empire held dominion over commerce in the Indian Ocean and South Atlantic. Portuguese sailors set out to reach Eastern Asia, landing in Taiwan, Japan, Timor, Flores, and the Moluccas. Although it was believed the Dutch were the first Europeans to arrive in Australia, there is evidence the Portuguese may have discovered it in 1521.[59][60][61]

Between 1519 and 1522 Ferdinand Magellan organised a Spanish expedition to the East Indies which resulted in the first circumnavigation of the globe. The Treaty of Zaragoza, signed in 1529 between Portugal and Spain, divided the Pacific Ocean between Spain and Portugal.[62]

Iberian Union and Restoration

Portugal voluntarily entered a dynastic union (1580–1640) because the last two kings of the House of Aviz died without heirs, resulting in the Portuguese succession crisis of 1580. Philip II of Spain claimed the throne and was accepted as Philip I of Portugal. Portugal did not lose its formal independence, forming a union of kingdoms. But the joining of the two crowns deprived Portugal of an independent foreign policy, and led to its involvement in the Eighty Years' War between Spain and the Netherlands.

War led to a deterioration of relations with Portugal's oldest ally, England, and the loss of Hormuz, a strategic trading post located between Iran and Oman. From 1595 to 1663 the Dutch-Portuguese War primarily involved Dutch companies invading Portuguese colonies and commercial interests in Brazil, Africa, India and the Far East, resulting in the loss of Portugal's Indian sea trade monopoly.

In 1640 John IV of Portugal spearheaded an uprising backed by disgruntled nobles and was proclaimed king. The Portuguese Restoration War ended the 60-year period of the Iberian Union under the House of Habsburg. This was the beginning of the House of Braganza, which reigned until 1910. John V saw a reign characterized by the influx of gold into the royal treasury, supplied largely by the royal fifth (tax on precious metals) from the Portuguese colonies of Brazil and Maranhão. Most estimates place the number of Portuguese migrants to Colonial Brazil during the gold rush of the 18th century at 600,000.[63] This represented one of the largest movements of European populations to their colonies, during colonial times.

Pombaline era and Enlightenment

In 1738 Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, later ennobled as 1st Marquis of Pombal, began a career as the Portuguese Ambassador in London, later in Vienna. King Joseph I was crowned in 1750 and made him his Minister of Foreign Affairs. As the King's confidence in Carvalho e Melo increased, he entrusted him with more control of the state. By 1755, Carvalho e Melo was made prime minister. Impressed by British economic success witnessed as Ambassador, he successfully implemented similar economic policies in Portugal.

In 1761, during the reign of King José I, he banned the import of black slaves into mainland Portugal and India, not for humanitarian reasons, but because they were a necessary work force in Brazil. At the same time, he encouraged the trade of black slaves ("the pieces", in the terms of that time) to that colony, and with the support and direct involvement of the Marquis of Pombal, two companies were founded - the Companhia do Grão-Pará e Maranhão and the Companhia Geral de Pernambuco e Paraíba - whose main activity was the trafficking of slaves, mostly Africans, to Brazilian lands.[64][65]

He reorganised the army and navy and ended legal discrimination against different Christian sects.[citation needed] He created companies and guilds to regulate commercial activity and one of the first appellation systems by demarcating the region for production of Port to ensure the wine's quality. This was the first attempt to control wine quality and production in Europe. He imposed strict law upon all classes of Portuguese society, along with a widespread review of the tax system. These reforms gained him enemies in the upper classes.

Lisbon was struck by a major earthquake on November 1st 1755, magnitude estimated to have been between 7.7–9.0, with casualties ranging from 12,000 to 50,000.[66] Following the earthquake, Joseph I gave his prime minister more power, and Carvalho de Melo became an enlightened despot. In 1758 Joseph I was wounded in an attempted assassination. The Marquis of Távora, several members of his family and even servants were tortured and executed in public with extreme brutality (even by the standards of the time), as alleged part of the Távora affair.[67][68][69]

The following year, the Jesuits were suppressed and expelled. This crushed opposition by publicly demonstrating even the aristocracy was powerless before Pombal. Further titled "Marquês de Pombal" in 1770, he ruled Portugal until Joseph I's death in 1777. The new ruler, Queen Maria I of Portugal, disliked Pombal because of his excesses, and upon her accession to the throne, withdrew all his political offices. Pombal was banished to his estate at Pombal, where he died in 1782.

Historians argue that Pombal's "enlightenment," while far-reaching, was primarily a mechanism for enhancing autocracy at the expense of individual liberty and especially an apparatus for crushing opposition, suppressing criticism, and furthering colonial exploitation and consolidating personal control, and profit.[70]

Crises of the 19th century

In 1807 Portugal refused Napoleon's demand to accede to the Continental System of embargo against the United Kingdom; a French invasion under General Junot followed, and Lisbon was captured in 1807. British intervention in the Peninsular War helped maintain Portuguese independence; the last French troops were expelled in 1812.[71]

Rio de Janeiro in Brazil was the Portuguese capital between 1808 and 1821. In 1820, constitutionalist insurrections took place at Porto and Lisbon. Lisbon regained its status as the capital of Portugal when Brazil declared its independence in 1822. The death of King John VI in 1826 led to a crisis of royal succession. His eldest son, Pedro I of Brazil, briefly became Pedro IV of Portugal, but neither the Portuguese nor Brazilians wanted a unified monarchy; consequently, Pedro abdicated the Portuguese crown in favor of his 7-year-old daughter, Maria da Glória, on the condition that when she came of age she would marry his brother, Miguel. Dissatisfaction at Pedro's constitutional reforms led the "absolutist" faction of landowners and the church to proclaim Miguel king in February 1828. This led to the Liberal Wars, also known as the War of the Two Brothers or the Portuguese Civil War, in which Pedro forced Miguel to abdicate and go into exile in 1834 and place his daughter on the throne as Queen Maria II of Portugal.

After 1815 the Portuguese expanded their trading ports along the African coast, moving inland to take control of Angola and Mozambique. The slave trade was abolished in 1836. In Portuguese India, trade flourished in the colony of Goa, with its subsidiary colonies of Macau, near Hong Kong, and Timor, north of Australia. The Portuguese successfully introduced Catholicism and the Portuguese language into their colonies, while most settlers continued to head to Brazil.[72][73]

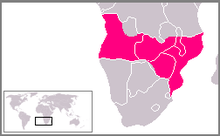

On 11 January 1890, the British government delivered an ultimatum to Portugal, demanding the withdrawal of Portuguese forces from the area between Portugal's colonies of Mozambique and Angola. The area had been claimed by Portugal as part of its colonialist Pink Map project, but Britain disputed these claims, mostly due to Cecil Rhodes' aspirations to create a Cape to Cairo Railway, which was intended to link all British colonies via a single railway. The government of Portugal quietly accepted the ultimatum and withdrew their forces from the disputed area, leading to a widespread backlash among the Portuguese public, who viewed acceptance of the British demands as a humiliation.[74]

First Republic and Estado Novo

On 5 October 1910, a coup d'état overthrew the near 800 year-old Monarchy and the Republic was proclaimed. During World War I, Portugal helped the Allies fight the Central Powers; however the war hurt its weak economy. Political instability and economic weaknesses were fertile ground for chaos and unrest during the First Portuguese Republic. These conditions led to the failed Monarchy of the North, 28 May 1926 coup d'état, and creation of the National Dictatorship (Ditadura Nacional). This in turn led to the right-wing dictatorship of the Estado Novo (New State), under António de Oliveira Salazar in 1933.

Portugal remained neutral in World War II. From the 1940s to 1960s, Portugal was a founding member of NATO, OECD, the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) and joined the United Nations in 1955. New economic development projects and relocation of mainland Portuguese citizens into the overseas provinces in Africa were initiated, with Angola and Mozambique being the main targets of those initiatives. These actions were used to affirm Portugal's status as a transcontinental nation and not a colonial empire.

Pro-Indian residents of Dadra and Nagar Haveli, separated those territories from Portuguese rule in 1954.[75] In 1961, Fort of São João Baptista de Ajudá's annexation by the Republic of Dahomey was the start of a process that led to the dissolution of the centuries-old Portuguese Empire. Another forcible retreat occurred in 1961 when Portugal refused to relinquish Goa. The Portuguese were involved in armed conflict in Portuguese India against the Indian Armed Forces. The operations resulted in the defeat and loss of the remaining Portuguese territories in the Indian subcontinent. The Portuguese regime refused to recognise Indian sovereignty over the annexed territories, which continued to be represented in the National Assembly until the coup of 1974.

Also in the early 1960s the independence movements in the Portuguese provinces of Portuguese Angola, Portuguese Mozambique, and Portuguese Guinea in Africa, resulted in the Portuguese Colonial War (lasting from 1961 till 1974). The war mobilised around 1.4 million men for military or for civilian support service,[76] and led to large casualties. Throughout the colonial war period Portugal dealt with increasing dissent, arms embargoes and other punitive sanctions imposed by the international community. The authoritarian and conservative Estado Novo regime, first governed by Salazar and from 1968 by Marcelo Caetano, tried to preserve the empire.[77]

Carnation Revolution and return to democracy

The government and army resisted the decolonization of its overseas territories until April 1974, when a left-wing military coup in Lisbon, the Carnation Revolution, led the way for the independence of territories, as well as the restoration of democracy after two years of a transitional period known as PREC (Processo Revolucionário Em Curso). This period was characterised by power disputes between left- and right-wing political forces. By the summer of 1975, the tensions were so high, that the country was on the verge of civil war. Forces connected to the extreme left-wing launched another coup on 25 November, but a military faction, the Group of Nine, initiated a counter-coup.

The Group of Nine emerged victorious, preventing the establishment of a communist state and ending political instability. The retreat from the overseas territories prompted a mass exodus of Portuguese citizens from its African territories.[78][79] Over one million Portuguese refugees fled the former Portuguese provinces, as white settlers were usually not considered part of the former colonies. By 1975, all Portuguese African territories were independent and Portugal held its first democratic elections in 50 years.

Portugal continued to be governed by a National Salvation Junta until the Portuguese legislative election of 1976. It was won by the Portuguese Socialist Party and Mário Soares, its leader, became prime minister. Soares would be prime minister from 1976 to 1978 and 1983 to 1985. Soares tried to resume the economic growth and development record that had been achieved before the Carnation Revolution. He initiated the process of accession to the European Economic Community (EEC).

After the transition to democracy, Portugal flipped between socialism and adherence to the neoliberal model. Land reform and nationalisations were enforced; the Portuguese Constitution was rewritten to accommodate socialist and communist principles. Until the revisions of 1982 and 1989, the constitution had references to socialism, the rights of workers, and the desirability of a socialist economy. Portugal's economic situation after the revolution obliged the government to pursue International Monetary Fund (IMF)-monitored stabilisation programmes in 1977–78 and 1983–85.

In 1986 Portugal alongside Spain, joined the European Economic Community which later became the European Union (EU). Portugal's economy progressed considerably as a result of European Structural and Investment Funds and companies' easier access to foreign markets.

Portugal's last overseas territory, Macau, was peacefully handed over to China in 1999. In 2002, the independence of East Timor (Asia) was formally recognised by Portugal. In 1995, Portugal started to implement Schengen Area rules, eliminating border controls with other Schengen members. Expo '98 took place in Portugal and in 1999 it was one of the founding countries of the euro and eurozone. In 2004 José Manuel Barroso, the then Prime Minister of Portugal, was nominated President of the European Commission. On 1 December 2009 the Treaty of Lisbon entered into force, enhancing the efficiency and democratic legitimacy of the Union. Economic disruption and an unsustainable growth in government debt during the financial crisis of 2007–2008 led the country to negotiate in 2011 with the IMF and the European Union, through the European Financial Stability Mechanism and the European Financial Stability Facility, a loan to help the country stabilise its finances.

Geography

Portugal occupies an area on the Iberian Peninsula (referred to as the continent by most Portuguese) and two archipelagos in the Atlantic Ocean: Madeira and the Azores. It lies between latitudes 30° and 42° N, and longitudes 32° and 6° W.

Continental Portugal is split by its main river, the Tagus, that flows from Spain and disgorges in the Tagus Estuary at Lisbon, before escaping into the Atlantic. The northern landscape is mountainous towards the interior with several plateaus indented by river valleys, whereas the south, including the Algarve and the Alentejo regions, is characterized by rolling plains.[80]

Portugal's highest peak is Mount Pico on Pico Island in the Azores. The archipelagos of Madeira and the Azores are scattered within the Atlantic Ocean: the Azores straddling the Mid-Atlantic Ridge on a tectonic triple junction, and Madeira along a range formed by in-plate hotspot geology. Geologically, these islands were formed by volcanic and seismic events. The last terrestrial volcanic eruption occurred in 1957–58 (Capelinhos) and minor earthquakes occur sporadically.

The exclusive economic zone, a sea zone over which the Portuguese have special rights in exploration and have use of marine resources, covers an area of 1,727,408 km2 (666,956 sq mi). This is the 3rd largest exclusive economic zone of the European Union and the 20th largest in the world.[81]

Provinces of Portugal

The term "provinces" (Portuguese: províncias) has been used throughout history to identify regions of continental Portugal. Current legal subdivisions of Portugal do not coincide with the provinces, but several provinces, in their 19th- and 20th-century versions, still correspond to culturally relevant, strongly self-identifying categories. They include:

- Alentejo (Alto Alentejo, Baixo Alentejo)

- Algarve

- Beira (Beira Alta, Beira Baixa, Beira Litoral)

- Douro Litoral

- Estremadura

- Minho

- Ribatejo

- Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro

The islands of Azores and Madeira were never called "provinces".

Climate

Portugal is mainly characterised by a Mediterranean climate,[82] temperate maritime climate in high altitude zones of the Azorean islands; a semi-arid climate in parts of the Beja District far south and in Porto Santo Island, a hot desert climate in the Selvagens Islands and a humid subtropical climate in the western Azores, according to the Köppen-Geiger climate classification. It is one of the warmest countries in Europe: the average temperature in mainland Portugal varies from 10–12 °C (50.0–53.6 °F) in the mountainous interior north to 17–19 °C (62.6–66.2 °F) in the south and on the Guadiana river basin. There are variations from the highlands to the lowlands.[83] The Algarve, separated from the Alentejo region by mountains reaching up to 900 metres (3,000 ft) in Alto da Fóia, has a climate similar to that of the southern coastal areas of Spain or Southwest Australia.

Annual average rainfall in the mainland varies from just over 3,200 millimetres (126.0 in) on the Peneda-Gerês National Park to less than 500 millimetres (19.7 in) in southern parts of Alentejo. Mount Pico receives the largest annual rainfall (over 6,250 millimetres (246.1 in) per year), according to Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera. In some areas, such as the Guadiana basin, annual diurnal average temperatures can be as high as 24.5 °C (76.1 °F), and summer's highest temperatures are routinely over 40 °C (104 °F). The record high of 47.4 °C (117.3 °F) was recorded in Amareleja.[84][85]

Snowfalls occur regularly, in the winter, in the interior North and Centre, particularly on the mountains. In winter, temperatures may drop below −10.0 °C (14.0 °F). In these places snow can fall any time from October to May. In the South snowfalls are rare but still occur in the highest elevations. While the official absolute minimum by IPMA is −16.0 °C (3.2 °F) in Penhas da Saúde and Miranda do Douro, lower temperatures have been recorded. Continental Portugal receives around 2,300-3,200 hours of sunshine annually, an average of 4–6 hours in winter and 10–12 hours in the summer, with higher values in the south-east, south-west, Algarve coast and lower in the north-west.

Portugal's central west and southwest coasts have an extreme ocean seasonal lag; sea temperatures are warmer in October than in July and are their coldest in March. The average sea surface temperature on the west coast of mainland Portugal varies from 14–16 °C (57.2–60.8 °F) in January−March to 19–21 °C (66.2–69.8 °F) in August−October while on the south coast it ranges from 16 °C (60.8 °F) in January−March and rises in the summer to about 22–23 °C (71.6–73.4 °F), occasionally reaching 26 °C (78.8 °F).[86] In the Azores, around 16 °C (60.8 °F) in February−April to 22–24 °C (71.6–75.2 °F) in July−September,[87] and in Madeira, around 18 °C (64.4 °F) in February−April to 23–24 °C (73.4–75.2 °F) in August−October.[88]

Azores and Madeira have a subtropical climate, although variations between islands exist. The Madeira and Azorean archipelagos have a narrower temperature range, with annual average temperatures exceeding 20 °C (68 °F) in some parts of the coast.[89] Some islands in Azores have drier months in the summer. Consequently, the islands of the Azores have been identified as having a Mediterranean climate, while some islands (such as Flores or Corvo) are classified as Humid subtropical, transitioning into an Oceanic climate at higher altitudes. Porto Santo Island in Madeira has a warm semi-arid climate. The Savage Islands, which are part of the regional territory of Madeira and a nature reserve are unique in being classified as a desert climate with an annual average rainfall of approximately 150 millimetres (5.9 in).

Biodiversity

Portugal is located on the Mediterranean Basin, the third most diverse hotspot of flora in the world.[90] It is home to six terrestrial ecoregions: Azores temperate mixed forests, Cantabrian mixed forests, Madeira evergreen forests, Iberian sclerophyllous and semi-deciduous forests, Northwest Iberian montane forests, and Southwest Iberian Mediterranean sclerophyllous and mixed forests.[91] Over 22% of its land area is included in the Natura 2000 network.[92][90] Eucalyptus, cork oak and maritime pine together make up 71% of the total forested area of continental Portugal.[93] Wildfires are quite common and a major issue in Portugal,[94] being the country with the highest percentage of burned area, on average, in the entire European Union.[95]

Geographical and climatic conditions facilitate the introduction of exotic species that later turn to be invasive and destructive to the native habitats. Around 20 percent of the total number of extant species in continental Portugal are exotic.[96] Portugal is the second country in Europe with the highest number of threatened animal and plant species.[97][98] Portugal as a whole is an important stopover for migratory bird species.[99][100]

The large mammalian species of Portugal (deer, Iberian ibex, wild boar, red fox, Iberian wolf and Iberian lynx) were once widespread throughout the country, but intense hunting, habitat degradation and growing pressure from agriculture and livestock reduced population on a large scale in the 19th and early 20th century, others, such as the Portuguese ibex were even led to extinction. Today, these animals are re-expanding their native range.[101][102]

The Portuguese west coast is part of the four major Eastern Boundary Upwelling Systems of the ocean. This seasonal upwelling system typically seen during the summer months brings cooler, nutrient rich water up to the sea surface promoting phytoplankton growth, zooplankton development and the subsequent rich diversity in pelagic fish and other marine invertebrates.[103] This makes Portugal one of the largest per capita fish-consumers in the world.[104] 73% of the freshwater fish occurring in the Iberian Peninsula are endemic, the largest out of any region in Europe.[105] Some protected areas of Portugal include: the Serras de Aire e Candeeiros,[106] the Southwest Alentejo and Vicentine Coast Natural Park,[107] and the Montesinho Natural Park which hosts some of the only populations of Iberian wolf and Iberian brown bear.[108]

Politics

Portugal has been a semi-presidential representative democratic republic since the ratification of the Constitution of 1976, with Lisbon, the nation's largest city, as its capital.[109] The Constitution grants the division or separation of powers among four sovereignty bodies: the President of the Republic, the Assembly of the Republic, the Government and the Courts.[110]

The Head of State is the President of the Republic, elected to a five-year term by direct, universal suffrage; the current president is Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa. Although largely a ceremonial post,[111] Presidential powers include the appointment of the Prime Minister and other members of the Government; dismissing the Prime Minister; dissolving the Assembly; vetoing legislation (which may be overridden by the Assembly); and declaring war (only on the advice of the Government and with the authorisation of the Assembly).[112] The President has also supervisory and reserve powers and is the ex officio Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces. The President is advised on issues of importance by the Council of State.[113]

Government

The Assembly of the Republic is a single chamber parliament composed of a maximum of 230 deputies elected for a four-year term.[114] The Government is headed by the Prime Minister and includes Ministers and Secretaries of State, that have full executive powers;[115] the current prime minister is Luís Montenegro.[116] The Council of Ministers – under the Prime Minister (or the President at the latter's request) and the Ministers – acts as the cabinet.[117] The Courts are organized into several levels, among the judicial, administrative and fiscal branches. The Supreme Courts are institutions of last resort/appeal. A thirteen-member Constitutional Court oversees the constitutionality of the laws.[118]

Portugal operates a multi-party system of competitive legislatures/local administrative governments at the national, regional and local levels. The Assembly of the Republic, Regional Assemblies and local municipalities and parishes, are dominated by two political parties, the Social Democratic Party and the Socialist Party, in addition to Enough, the Liberal Initiative, the Left Bloc, the Unitary Democratic Coalition (Portuguese Communist Party and Ecologist Party "The Greens"), LIVRE, the CDS – People's Party and the People Animals Nature.[119]

Foreign relations

A member state of the United Nations since 1955, Portugal is a founding member of NATO (1949), the OECD (1961) and EFTA (1960); it left the last in 1986 to join the European Economic Community, which became the European Union in 1993. In 1996, Portugal co-founded the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP), also known as the Lusophone Commonwealth, an international organisation and political association of Lusophone nations where Portuguese is an official language.

Portugal was a full member of the Latin Union (1983) and the Organisation of Ibero-American States (1949). It has a friendship alliance and dual citizenship treaty with its former colony, Brazil. Portugal and the United Kingdom share the world's oldest active military accord through their Anglo-Portuguese Alliance (Treaty of Windsor), signed in 1373.

Territorial disputes

Olivenza: Under Portuguese sovereignty since 1297, the municipality of Olivença was ceded to Spain under the Treaty of Badajoz in 1801, after the War of the Oranges. Portugal claimed it back in 1815 under the Treaty of Vienna. However, since the 19th century, it has been continuously ruled by Spain which considers the territory theirs not only de facto but also de jure.[120]

Savage Islands: A small group of mostly uninhabited islets which fall under Portuguese Madeira's regional autonomous jurisdiction. Found in 1364 by Italian mariners under the service of Prince Henry The Navigator,[121] it was first noted by Portuguese navigator Diogo Gomes de Sintra in 1438. Historically, the islands have belonged to private Portuguese owners from the 16th century on, until 1971[122] when the government purchased them and established a natural reserve area covering the whole archipelago. The islands have been claimed by Spain since 1911,[123] and the dispute has caused some periods of political tension between the two countries.[124] The main problem for Spain's attempts to claim these small islands, has been not so much their intrinsic value, but the fact that they expand Portugal's exclusive economic zone considerably to the south, in detriment of Spain.[125] The Selvagens Islands have been tentatively added to UNESCO's world heritage list in 2017.[126]

Military

The armed forces have three branches: Navy, Army and Air Force, commanded by the Portuguese Armed Forces General Staff. They serve primarily as a self-defence force whose mission is to protect the territorial integrity of the country but can also be used in offensive missions in foreign territories.[127] In recent years, the Portuguese Armed Forces have carried out several NATO and European Union military missions in various territories, namely in Afghanistan, Iraq, Lebanon, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Mali, Central African Republic, Somalia, Mozambique and East Timor. As of 2023, the three branches numbered 24.000 military personnel. Portuguese military expenditure in 2023 was more than 4 billion US$, representing 1.48 per cent of GDP.[128]

The Army of 11,000 personnel comprises three brigades and other small units. An Infantry Brigade (mainly equipped with Pandur II APC, M114 howitzer and MIM-72 Chaparral air defence systems), a Mechanized Brigade (mainly equipped with Leopard 2 A6 tanks and M113A2 APC) and a Rapid Reaction Brigade (consisting of Paratroopers, Commandos, Rangers and Artillery Regiment). The Navy (7,000 personnel, of which 900 are marines), the world's oldest surviving naval force, has five frigates, two corvettes, two submarines, and 20 oceanic patrol vessels. The Air Force (6,000 personnel) has the Lockheed F-16M Fighting Falcon as the main combat aircraft.

In addition to the three branches of the armed forces, there is the National Republican Guard, a security force subject to military law and organisation (gendarmerie) comprising 25,000 personnel. This force is under the authority of both the Defence and the Interior Ministry. It has provided detachments for participation in international operations in Iraq and East Timor. The United States maintains a military presence with 770 troops in the Lajes Air Base at Terceira Island, in the Azores. The Allied Joint Force Command Lisbon (JFC Lisbon) is one of the three main subdivisions of NATO's Allied Command Operations.

Law and justice

The Portuguese legal system is part of the civil law legal system. The main laws include the Constitution (1976), the Portuguese Civil Code (1966) and the Penal Code of Portugal (1982), as amended. Other relevant laws are the Commercial Code (1888) and the Civil Procedure Code (1961). Portuguese laws were applied in the former colonies and territories and continue to be influences for those countries. The supreme national courts are the Supreme Court of Justice and the Constitutional Court. The Public Ministry, headed by the Attorney General of the Republic, constitutes the independent body of public prosecutors.

Drug decriminalisation was declared in 2001, making Portugal the first country to allow usage and personal possession of all common drugs. Despite criticism from other European nations, who stated Portugal's drug consumption would tremendously increase, overall drug use has declined along with HIV infection cases, which dropped 50 percent by 2009. Overall drug use among 16- to 18-year-olds declined, however use of marijuana rose slightly.[129][130][131]

LGBT rights in Portugal have increased substantially in the 21st century. In 2003, Portugal added an anti-discrimination employment law on the basis of sexual orientation.[132] In 2004, sexual orientation was added to the Constitution as part of the protected from discrimination characteristics.[133] In 2010, Portugal became the sixth country in Europe and eighth in the world to legalize same-sex marriage at the national level.[134]

LGBT adoption has been allowed since 2016[135] as has female same-sex couple access to medically assisted reproduction.[136] In 2017 the Law of Gender Identity,[137] simplified the legal process of gender and name change for transgender people, making it easier for minors to change their sex marker in legal documents.[138] In 2018, the right to gender identity and gender expression self-determination became protected, intersex minors became protected by law from unnecessary medical procedures "until the minor gender identity manifests" and the right of protection from discrimination on the basis of sex characteristics became protected by the same law.[139]

Euthanasia has been legalised after reviews in parliament. Nationals over 18 who are terminally ill and in extreme suffering, but who can still decide to, will have the legal right to request assisted dying. However, non-residents will not.[140] Despite the Parliamentary approval, Euthanasia legislation is yet to be regulated and a timeline for it is still unknown, meaning that Euthanasia is currently on hold.[141]

Law enforcement

Portugal's main police organisations are the Guarda Nacional Republicana – GNR (National Republican Guard), a gendarmerie; the Polícia de Segurança Pública – PSP (Public Security Police), a civilian police force who work in urban areas; and the Polícia Judiciária – PJ (Judicial Police), a highly specialised criminal investigation police that is overseen by the Public Ministry.

Portugal has 49 correctional facilities in total run by the Ministry of Justice. They include seventeen central prisons, four special prisons, twenty-seven regional prisons, and one 'Cadeia de Apoio' (Support Detention Centre).[142] As of 1 January 2023[update], their current prison population is about 12,257 inmates, which comes to about 0.12% of their entire population.[143] The incarceration rate has been on the rise since 2010, with a 15% increase over the past eight years.[144]

Administrative divisions

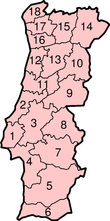

Administratively, Portugal is divided into 308 municipalities (municípios or concelhos), which after a reform in 2013 are subdivided into 3,092 civil parishes (Portuguese: freguesia). Operationally, the municipality and civil parish, along with the national government, are the only legally local administrative units identified by the government of Portugal (for example, cities, towns or villages have no standing in law, although may be used as catchment for the defining services). Continental Portugal is agglomerated into 18 districts, while the archipelagos of the Azores and Madeira are governed as autonomous regions; the largest units, established since 1976, are either mainland Portugal and the autonomous regions of Portugal (Azores and Madeira).

The 18 districts of mainland Portugal are: Aveiro, Beja, Braga, Bragança, Castelo Branco, Coimbra, Évora, Faro, Guarda, Leiria, Lisbon, Portalegre, Porto, Santarém, Setúbal, Viana do Castelo, Vila Real and Viseu – each district takes the name of the district capital.

Within the European Union NUTS system, Portugal is divided into nine regions:[145] the Azores, Alentejo, Algarve, Centro, Lisboa, Madeira, Norte, Oeste e Vale do Tejo and Península de Setúbal, and with the exception of the Azores and Madeira, NUTS areas are subdivided into 28 subregions. Population estimates from 2023.

| Region | Capital | Area | Population | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | North Region | Porto | 21,278 km2 (8,215 sq mi) | 3,673,861 | |

| 2 | Central Region | Coimbra | 22,636 km2 (8,740 sq mi) | 1,695,635 | |

| 3 | West and Tagus Valley | Santarém | 9,839 km2 (3,799 sq mi) | 852,583 | |

| 4 | Greater Lisbon | Lisbon | 1,580 km2 (610 sq mi) | 2,126,578 | |

| 5 | Setúbal Peninsula | Setúbal | 1,421 km2 (549 sq mi) | 834,599 | |

| 6 | Alentejo Region | Évora | 27,329 km2 (10,552 sq mi) | 474,701 | |

| 7 | Algarve Region | Faro | 4,997 km2 (1,929 sq mi) | 484,122 | |

| 8 | Madeira Autonomous Region | Funchal | 801 km2 (309 sq mi) | 256,622 | |

| 9 | Azores Autonomous Region | Ponta Delgada | 2,351 km2 (908 sq mi) | 241,025 |

| District | Area | Population |

|

District | Area | Population | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lisbon | 2,761 km2 (1,066 sq mi) | 2,355,867 | 10 | Guarda | 5,518 km2 (2,131 sq mi) | 141,995 | |

| 2 | Leiria | 3,517 km2 (1,358 sq mi) | 479,261 | 11 | Coimbra | 3,947 km2 (1,524 sq mi) | 418,136 | |

| 3 | Santarém | 6,747 km2 (2,605 sq mi) | 441,255 | 12 | Aveiro | 2,808 km2 (1,084 sq mi) | 725,461 | |

| 4 | Setúbal | 5,064 km2 (1,955 sq mi) | 902,863 | 13 | Viseu | 5,007 km2 (1,933 sq mi) | 355,309 | |

| 5 | Beja | 10,225 km2 (3,948 sq mi) | 148,881 | 14 | Bragança | 6,608 km2 (2,551 sq mi) | 122,739 | |

| 6 | Faro | 4,960 km2 (1,915 sq mi) | 484,122 | 15 | Vila Real | 4,328 km2 (1,671 sq mi) | 185,086 | |

| 7 | Évora | 7,393 km2 (2,854 sq mi) | 153,475 | 16 | Porto | 2,395 km2 (925 sq mi) | 1,846,178 | |

| 8 | Portalegre | 6,065 km2 (2,342 sq mi) | 104,081 | 17 | Braga | 2,673 km2 (1,032 sq mi) | 863,547 | |

| 9 | Castelo Branco | 6,675 km2 (2,577 sq mi) | 179,608 | 18 | Viana do Castelo | 2,255 km2 (871 sq mi) | 234,215 |

Economy

Portugal is a developed and high-income country[148][149][150] with a GDP per capita of 83% of the EU27 average in 2023, and a HDI of 0.874 (the 42nd highest in the world) in 2021.[151][152] It holds the 13th largest gold reserve in the world at its national central bank,[153] has the 8th largest proven reserves of lithium,[154][155][156] with total exports representing 47.4% of its GDP in 2023.[157] Portugal has been a net beneficiary of the European Union budget since it joined the union, then known as EEC, in 1986.[158][159][160][161]

By the end of 2023, GDP (PPP) was $48,759 per capita, according to the World Bank.[162] In 2023, Portugal had the 5th lowest GDP per capita (PPP) of the eurozone out of 20 members, and the 8th lowest of the European Union out of 27 member-states.[163] In 2022, labour productivity had fallen to the fourth lowest among the 27 member-states of the European Union (EU) and was 35% lower than the EU average.[164] Within the EU, Portugal's economy ranks lower than most Western states.[165]

Portugal was an original member of the eurozone. The national currency, the euro (€) started transitioning from the Portuguese Escudo in 2000 and consolidated in 2002. Portugal's central bank is the Banco de Portugal, an integral part of the European System of Central Banks. Most industries, businesses and financial institutions are concentrated in the Lisbon and Porto metropolitan areas – the Setúbal, Aveiro, Braga, Coimbra, Leiria and Faro districts are the biggest economic centres outside these two main areas.

Since the Carnation Revolution of 1974, which culminated in the end of one of Portugal's most notable phases of economic expansion,[166] a significant change has occurred in the nation's annual economic growth.[167] After the turmoil of the 1974 revolution, Portugal tried to adapt to a changing modern global economy, a process that continues. Since the 1990s, Portugal's public consumption-based economic development model has changed to a system focused on exports, private investment and the development of the high-tech sector. Consequently, business services have overtaken more traditional industries such as textiles, clothing, footwear and cork (Portugal is the world's leading cork producer),[168] wood products and beverages.[169]

In the 2010s, the Portuguese economy suffered its most severe recession since the 1970s, which resulted in the country receiving a 78-billion-euro bailout from the European Union and the International Monetary Fund in May 2011.[170] At the end of 2023, the share of debt as percentage of GDP fell below 100 percent, to 97.9%.[171]

As of 2023, the average salary in the private sector was €1,505 per month,[172] and the minimum wage, which is regulated by law, is €870 per month (paid 14 times per annum) as of 2025.[173] The Global Competitiveness Report for 2019, published by the World Economic Forum, placed Portugal 34th. The Numbeo quality of life index placed Portugal 20th in the world in 2023.[150]

Companies listed on Euronext Lisbon stock exchange like EDP, Galp, Jerónimo Martins, Mota-Engil, Novabase, Semapa, Portucel Soporcel, Portugal Telecom and Sonae, are among the largest corporations by number of employees, net income or international market share. The Euronext Lisbon is the major stock exchange and part of the pan-European group of stock exchanges Euronext. The PSI-20 is Portugal's most selective and widely known stock index.

The OECD economic reports since 2018 show recovery.[174][175][176] Rents and house prices have skyrocketed in Portugal, particularly Lisbon, where rents jumped 37% in 2022. The 8% inflation rate in the same year exacerbated the problem.[177] According to the IMF, Portugal's economic recovery from the COVID pandemic in 2022 was substantially better than the EU average. Although modest, economic growth continued in 2023 while inflation continued decreasing to 5%.[178][179] In 2024 the annual inflation level is forecast at 2.3% accompanied by a small economic growth.[180][181]

Agriculture in Portugal is based on small to medium-sized family-owned dispersed units. However, the sector also includes larger scale intensive farming, export-oriented agrobusinesses. The country produces a variety of crops and livestock products, including: tomatoes, citrus, green vegetables, rice, wheat, barley, maize, olives, oilseeds, nuts, cherries, bilberry, table grapes, edible mushrooms, dairy products, poultry and beef. According to FAO, Portugal is the top producer of cork and carob in the world, accounting for about 50% and 30% of world production, respectively.[182] It is the third largest exporter of chestnuts and third largest European producer of pulp.[183] Portugal is among the world's top ten largest olive oil producers and fourth largest exporter.[184] The country is one of the world's largest exporters of wine, reputed for its fine wines. Forestry has played an important economic role among the rural communities and industry. In 2001, the gross agricultural product accounted for 4% of the economy; in 2022 it was 2%.[185]

Tourism

Travel and tourism is an important part of Portugal's economy. As of 2023, nearly half of real GDP growth was due to the tourism sector, with tourism accounting for 16.5% of GDP.[186] It has been necessary for the country to focus upon its niche attractions, such as health, nature and rural tourism, to stay ahead of its competitors.[187]

Portugal is among the top 20 most-visited countries in the world, receiving more than 26,5 million foreign tourists by 2023.[188] In 2014, Portugal was elected The Best European Country by USA Today.[189] In 2017, Portugal was elected both Europe's Leading Destination[190] and in 2018 and 2019, World's Leading Destination[191]

Tourist hotspots in Portugal are: Lisbon, Cascais, Algarve, Madeira, Nazaré, Fátima, Óbidos, Porto, Braga, Guimarães and Coimbra. Lisbon attracts the sixteenth-most tourists among European cities[192] (with seven million tourists occupying the city's hotels in 2006).[193]

Science and technology

Scientific and technological research activities are mainly conducted within a network of R&D units belonging to public universities and state-managed autonomous research institutions like the INETI – Instituto Nacional de Engenharia, Tecnologia e Inovação and the INRB – Instituto Nacional dos Recursos Biológicos. Funding and management of this system is conducted under the authority of the Ministry of Science, Technology and Higher Education and the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (Foundation for Science and Technology). The largest R&D units of the public universities by volume of research grants and peer-reviewed publications, include biosciences research institutions.

Among the largest non-state-run research institutions are the Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência and the Champalimaud Foundation, a neuroscience and oncology research centre. National and multinational high-tech and industrial companies, are responsible for research and development projects. One of the oldest learned societies of Portugal is the Sciences Academy of Lisbon, founded in 1779.

Iberian bilateral state-supported research efforts include the International Iberian Nanotechnology Laboratory and the Ibercivis distributed computing platform. Portugal is a member of pan-European scientific organizations. These include the European Space Agency (ESA), the European Laboratory for Particle Physics (CERN), ITER, and the European Southern Observatory (ESO). Portugal has the largest aquarium in Europe, the Lisbon Oceanarium, and have other notable organizations focused on science-related exhibits and divulgation, like the state agency Ciência Viva,[194] the Science Museum of the University of Coimbra, the National Museum of Natural History at the University of Lisbon, and the Visionarium. The European Innovation Scoreboard 2011, placed Portugal-based innovation 15th, with increase in innovation expenditure and output.[195] Portugal was ranked 31st in the Global Innovation Index in 2024.[196]

Transport

Portugal has a 68,732 km (42,708 mi) road network, of which almost 3,000 km (1,864 mi) are part of system of 44 motorways. On many highways, a toll needs to be paid (see Via Verde). Vasco da Gama bridge is the longest bridge in the EU (the second longest in Europe) at 12.345 km (7.671 mi).[198][199]

Continental Portugal's 89,015 km2 (34,369 sq mi) territory is serviced by four international airports located near the principal cities of Lisbon, Porto, Faro and Beja. Lisbon's geographical position makes it a stopover for many foreign airlines at several airports within the country. The primary flag-carrier is TAP Air Portugal, although many other domestic airlines provide services within and without the country.

The most important airports are in Lisbon, Porto, Faro, Funchal (Madeira), and Ponta Delgada (Azores), managed by the national airport authority group ANA – Aeroportos de Portugal. A new airport, to replace the current Lisbon airport, has been planned for more than 50 years, but it has been always postponed by a series of reasons.[200]

A national railway system that extends throughout the country and into Spain, is supported and administered by Comboios de Portugal (CP). Rail transport of passengers and goods is derived using the 2,791 km (1,734 mi) of railway lines currently in service, of which 1,430 km (889 mi) are electrified and about 900 km (559 mi) allow train speeds greater than 120 km/h (75 mph). The railway network is managed by Infraestruturas de Portugal while the transport of passengers and goods are the responsibility of CP, both public companies. In 2006, the CP carried 133,000,000 passengers and 9,750,000 tonnes (9,600,000 long tons; 10,700,000 short tons) of goods.

The major seaports are located in Sines, Leixões, Lisbon, Setúbal, Aveiro, Figueira da Foz, and Faro. The two largest metropolitan areas have subway systems: Lisbon Metro and Metro Sul do Tejo light rail system in the Lisbon metropolitan area, and Porto Metro light metro system in the Porto Metropolitan Area, each with more than 35 km (22 mi) of lines. Coimbra is currently developing a Bus rapid transit system, Metro Mondego.

In Portugal, Lisbon tram services have been supplied by the Companhia de Carris de Ferro de Lisboa (Carris), for over a century. In Porto, a tram network, of which only a tourist line on the shores of the Douro remains, began construction on 12 September 1895 (a first for the Iberian Peninsula). All major cities and towns have their own local urban transport network, as well as taxi services.

Energy

Portugal has considerable resources of wind and hydropower. In 2006, the world's then largest solar power plant, the Moura Photovoltaic Power Station, began operating, while the world's first commercial wave power farm, the Aguçadoura Wave Farm, opened in the Norte region (2008). By 2006, 66% of the country's electrical production was from coal and fuel power plants, while 29% were derived from hydroelectric dams, and 6% by wind energy.[201] In 2008, renewable energy resources were producing 43% of the nation's electricity, even as hydroelectric production decreased with severe droughts.[202] As of 2010, electricity exports had outnumbered imports and 70% of energy came from renewable sources.[203]

Portugal's national energy transmission company, Redes Energéticas Nacionais (REN), uses modelling to predict weather, especially wind patterns. Before the solar/wind revolution, Portugal had generated electricity from hydropower plants on its rivers for decades. New programmes combine wind and water: wind-driven turbines pump water uphill at night; then water flows downhill by day, generating electricity, when consumer demand is highest. Portugal's distribution system is now two-way. It draws electricity small generators, like rooftop solar panels.

Demographics

- 0-49

- 50-99

- 100-499

- 500-999

- 1000-1999

- 2000+

Statistics Portugal (Portuguese: INE – Instituto Nacional de Estatística) estimates that, by 31 December 2023, the population was 10,639,726, of which 52.2% was female and 47.8% male.[10][204] In 2024 the median life expectancy was 82.8 years[205] and United Nations projections point to 90 or above, by 2100.[206] The population has been relatively homogeneous for most of its history, with a single religion (Catholic church) and language.

Despite good economic development, the Portuguese have been the shortest in Europe since around 1890. This emerging height gap started in the 1840s and increased. A driving factor was modest real wage growth, given late industrialization and economic growth compared to the European core. Another determinant was delayed human capital formation.[207]

Portugal has to deal with low fertility levels: the country has experienced a sub-replacement fertility rate since the 1980s.[208] The total fertility rate (TFR) as of 2024[update] was estimated at 1.36 children born/woman, one of the lowest in the world, similarly to countries such as Japan, South Korea, Italy, all well below the replacement rate of 2.1,[209][210] and considerably below the high of 5 children born per woman in 1911.[211] In 2016, 53% of births were to unmarried women.[212] Portugal's population has been steadily ageing and was the 11th oldest in the world, with a median age of 46 years in 2023. In the same year, it had the world's 4th highest number of citizens over 65 years, at 21.8% of the whole population.[213][214]

The structure of Portuguese society shows social inequality, which in 2019 placed the country 24th in the Social Justice Index, in the EU.[215] In 2018, Portugal's parliament approved a budget plan for 2019 that included tax breaks for returning emigrants in a bid to attract back those who left during the financial crisis of 2007–2008.[216] According to projections by the national statistics office, Portugal's population will fall to 7.7 million by 2080 from 10.6 million and the population will continue to age.[217]

According to a National Statistics Institute (INE) study, conducted shortly after the 2021 census, between 2022 and 2023, 6,4 million people aged between 18 and 74 years old identified themselves as White (84%), more than 262,000 identify as Mixed-race (3%), nearly 170,000 as Black (2%), 57,000 as Asian (<1%), and 47,500 as Romani (<1%)[218]

Urbanization

Based on commuting patterns, OECD and Eurostat define eight metropolitan areas of Portugal.[219] Only two have populations over 1 million, and since the 2013 local government reform, these are the only two which also have administrative legal status of metropolitan areas: Lisbon and Porto,[220][221] Several smaller metropolitan areas (Algarve, Aveiro, Coimbra, Minho and Viseu)[221] also held this status from 2003 to 2008, when they were converted into intermunicipal communities, whose territories are roughly based on the NUTS III statistical regions.[222][221]

| Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | Rank | Name | Region | Pop. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Lisbon  Sintra |

1 | Lisbon | Lisboa | 567,131 | 11 | Oeiras | Lisboa | 175,677 |  Vila Nova de Gaia  Porto |

| 2 | Sintra | Lisboa | 395,528 | 12 | Seixal | Lisboa | 173,163 | ||

| 3 | Vila Nova de Gaia | Norte | 311,223 | 13 | Gondomar | Norte | 168,582 | ||

| 4 | Porto | Norte | 248,769 | 14 | Guimarães | Norte | 156,789 | ||

| 5 | Cascais | Lisboa | 219,636 | 15 | Odivelas | Lisboa | 153,708 | ||

| 6 | Loures | Lisboa | 207,065 | 16 | Coimbra | Centro | 144,822 | ||

| 7 | Braga | Norte | 201,583 | 17 | Maia | Norte | 142,594 | ||

| 8 | Almada | Lisboa | 181,232 | 18 | Santa Maria da Feira | Norte | 139,837 | ||

| 9 | Matosinhos | Norte | 179,558 | 19 | Vila Franca de Xira | Lisboa | 139,452 | ||

| 10 | Amadora | Lisboa | 178,253 | 20 | Vila Nova de Famalicão | Norte | 135,994 | ||

Immigration

In 2023 Portugal had 10,639,726 inhabitants, of whom 1,044,606 accounted for legal resident foreigners[3][225] Resident foreigners make up approximately 10% of the population. These figures do not include Portuguese citizens of foreign descent, as in Portugal it is illegal to collect data based on ethnicity. For instance, more than 340,000 resident foreigners who acquired Portuguese citizenship between 2008 and 2022 - and thus constitute around 3.27% of the country's population in 2022 - were not taken into account in immigration figures as they became official Portuguese citizens.[226] In 2022 alone, almost 21,000 foreign residents acquired Portuguese citizenship, of which 11,170 were female and 9,674 were male.[227]

Portugal, for long a country of emigration (the vast majority of Brazilians have Portuguese ancestry),[228] became a country of net immigration.[229] The influx of immigrants didn't come just from the last Indian (Portuguese until 1961), African (Portuguese until 1975), and Far East Asian (Portuguese until 1999) overseas territories, but from other parts of the world as well. Even though in the aftermath of the COVID-19 Pandemic, Portugal's emigration rate increased to 6.9‰ in 2022, it was still well below the immigration rate of around 11.3‰.[230][231] It is also noteworthy that the overwhelming majority of Portuguese emigrants tend to leave the country for short periods, with 56.8% of those having left the country in 2022 doing so for less than a year.[232]

Since the 1990s, along with a boom in construction, several new waves of Ukrainian, Brazilian, Afro-Portuguese and other Africans have settled in the country. Romanians, Moldovans, Kosovo Albanians, Russians, Bulgarians, and Chinese have also migrated to the country. The numbers of Venezuelan, Pakistani, Indian, and Bangladeshi migrants are also significant. Moreover, Portugal's Romani population is estimated at 50,000.[233]

It is estimated that over 30,000 seasonal, often illegal immigrants work in agriculture, mainly southern cities such as Odemira where they are often exploited by organised seasonal workers' networks. These migrants, who frequently arrive without due documentation or work contracts, make up over 90% of agricultural workers in the south of Portugal. Most are Southeast Asians from India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Pakistan and Thailand. In the interior of the Alentejo there are many African workers. Significant numbers also come from Eastern Europe, Moldova, Ukraine, Romania and Brazil.[234]

In addition, a significant number of EU citizens, mostly from Italy, France, Germany or other northern European countries, have become permanent residents in the country.[235] There is also a large expatriate community made up of Britons, Canadians and people from the United States of America. The British community is mostly composed of retired pensioners who live in the Algarve and Madeira.

A National Statistics Institute (INE) study, conducted between 2022 and 2023, found out that 1.4 million people, (13% of the population) have immigrant background, in which 947,500 are first generation immigrants, concentrated mainly in the Lisbon metropolitan area and the Algarve.[218] It is noteworthy that the survey was only carried out amongst people living legally in the country for at least one year at the time of the interview and that in 2022 the statistical office figures suggested that 16.1% of the country's population or 1,683,829 people were first generation immigrants.[236][237][238]

Religion

Religion in Portugal (Census 2021)[4]

Roman Catholicism, which has a long history in Portugal, remains the dominant religion. Portugal has no official religion, though in the past, the Catholic Church in Portugal was the state religion.[239][240]

According to the 2021 Census, 80.2% of the Portuguese population was Roman Catholic Christian.[4] The country has small Protestant, Latter-day Saint, Muslim, Hindu, Sikh, Eastern Orthodox Church, Jehovah's Witnesses, Baháʼí, Buddhist, Jewish and Spiritist communities. Influences from African Traditional Religion and Chinese Traditional Religion are also felt among many people, particularly in fields related with Traditional Chinese Medicine and Traditional African Herbal Medicine. Some 14.1% of the population declared themselves to be non-religious.[4]

Portugal is a secular state: church and state were formally separated during the First Portuguese Republic, and this was reiterated in the 1976 Portuguese Constitution. Other than the Constitution, the two most important documents relating to religious freedom in Portugal are the 1940 Concordata (later amended in 1971) between Portugal and the Holy See and the 2001 Religious Freedom Act. Many Portuguese holidays, festivals and traditions have a Christian origin or connotation.

Languages

Portuguese is the official language of Portugal. Mirandese is also recognised as a co-official regional language in some municipalities of North-Eastern Portugal. It is part of the Astur-Leonese group of languages.[241] An estimate of between 6,000 and 7,000 Mirandese speakers has been documented for Portugal.[242] Furthermore, a particular dialect known as Barranquenho, spoken in Barrancos, is also officially recognised and protected in Portugal since 2021.[243] Minderico, a sociolect of the Portuguese language, is spoken by around 500 people in the town of Minde.[244]

According to the International English Proficiency Index, Portugal has a high proficiency level in English, higher than those of other Romance-speaking European countries like Spain, Italy or France.[245]

Education

The educational system is divided into preschool (for those under age six), basic education (nine years, in three stages, compulsory), secondary education (three years, compulsory since 2010), and higher education (subdivided in university and polytechnic education). Universities are usually organised into faculties. Institutes and schools are also common designations for autonomous subdivisions of Portuguese higher education institutions.

The total adult literacy rate in Portugal was 99.8% in 2021.[246] According to the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) 2018, Portugal scored around the OECD average in reading, mathematics and science.[247][248] In reading and mathematics, mean performance in 2018 was close to the level observed in 2009 to 2015; in science, mean performance in 2018 was below that of 2015, and returned close to the level observed in 2009 and 2012, near below average.[249][250][251]

About 47.6% of college-age citizens (20 years old) attend one of Portugal's higher education institutions[252][253][254] (compared with 50% in the United States and 35% in the OECD on average). In addition to being a destination for international students, Portugal is also among the top places of origin for international students. All higher education students, both domestic and international, totalled 380,937 in 2005.

Portuguese universities have existed since 1290. The oldest Portuguese university[255] was first established in Lisbon before moving to Coimbra. Historically, within the scope of the Portuguese Empire, the Portuguese founded the oldest engineering school of the Americas (the Real Academia de Artilharia, Fortificação e Desenho of Rio de Janeiro) in 1792, as well as the oldest medical college in Asia (the Escola Médico-Cirúrgica of Goa) in 1842. Presently, the largest university in Portugal is the University of Lisbon.

The Bologna process has been adopted by Portuguese universities and poly-technical institutes in 2006. Higher education in state-run educational establishments is provided on a competitive basis, a system of numerus clausus is enforced through a national database on student admissions. However, every higher education institution offers also a number of additional vacant places through other extraordinary admission processes for sportsmen, mature applicants (over 23 years old), international students, foreign students from the Lusosphere, degree owners from other institutions, students from other institutions (academic transfer), former students (readmission), and course change, which are subject to specific standards and regulations set by each institution or course department.

Most student costs are supported with public money. Portugal has entered into cooperation agreements with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and other US institutions to further develop and increase the effectiveness of Portuguese higher education and research.[256]

Health